On January 1, 2015, I started learning to draw.

I’d made a couple brief attempts before, but nothing very serious. I’d eyeballed some official Pokémon artwork on two occasions, and that was pretty much it. I’d been dating an artist for seven years and had been surrounded by artist friends for nearly half my life, but I’d never taken a real crack at it myself.

On some level, I didn’t believe I could. It seemed so far outside the range of things I was already any good at. I’m into programming and math and computers and puzzles; aesthetics are way on the opposite end of a spectrum that only exists inside my head. Is it possible to bridge that huge, imaginary gap? Is it even allowed? (Spoilers: totally.)

In the ensuing sixteen months, a lot of people have — repeatedly — expressed surprise at how fast I’ve improved. I’ve then — repeatedly — expressed surprise at this surprise, because I don’t feel like I’m doing anything particularly special. I don’t have any yardstick for measuring artistic improvement speed; the artists I’ve known have always been drawing for years by the time I first met them. Plenty of people start drawing in childhood; not so many start at 27.

On the other hand, I do have 15 years’ experience of being alright at a thing. I suspect, in that time, I’ve picked up a different kind of skill that’s undervalued, invaluable, and conspicuously lacking from any curriculum: how to learn!

I don’t claim to be great at art, or even necessarily great at learning, but here are some things I’ve noticed myself doing. I hope that writing this down will, at the very least, help me turn it into a more deliberate and efficient process — rather than the bumbling accident it’s been so far.

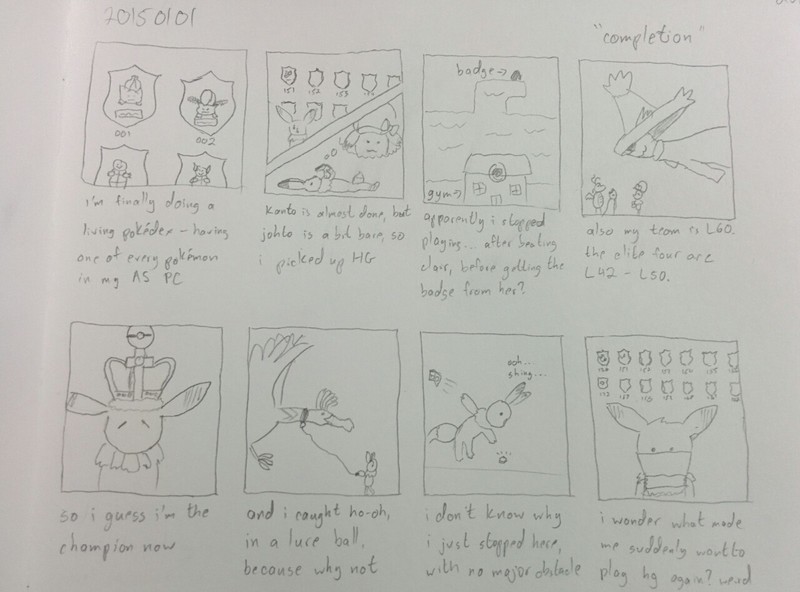

I started out doing daily comics, just because Mel was also doing them. The first one was… not terribly great. It hadn’t even occurred to me to bump the contrast on this photo.

At this point I was vaguely aware of some extreme basics:

- things are made of shapes

- faces are two dots with a mouth under them

- arms have some kinda little stubs at the end

- you can do a squiggle to kind of make fur

I’ve had people tell me I was already drawing better than them here. I can see how I might’ve had a tiny bit of a head start: I do live with two artists, and clumsy attempts at web design have given me a slight appreciation for whitespace and composition. Still, I don’t think this is wildly beyond anyone’s ability.

The most important thing was probably the idea of daily comics, which got me to draw at least one thing a day — several, in fact, since they’re comics. I kept this up through the end of March, at which point I just plain ran out of ideas for comics. There are only so many ways to draw “I worked on computer stuff and also my cat does funny things”. But that’s still 90 days, times an average of at least two panels per comic, which is hundreds of drawings. My first insight is thus:

Do the thing. Do it a lot. No, don’t “practice”. “Practice” sounds rote and repetitive; even reading the word makes me feel pre-emptively bored. Just do it. Find an excuse to do it. Any excuse. You want to write embarrassing fanfiction? Do it. You want to make four-chords pop songs? Do it. You don’t need to do something high-brow or rigorous or chosen from a careful gradient of boring beginner exercises. You just need to something.

Even better, do something regularly and release it publicly (or at least to a moderate circle of people). It helps to have some light pressure, and posting something every day starts to feel like it’s expected of you, even if you’ve never explicitly promised anything.

If it starts to feel like too much of a drag, you can always drop it and try something else. You can take a break for a while, you can do some personal work, you can do whatever self-hack will help you keep doing something.

Mel’s birthday is March 26. On March 19, 2015, our roommate gave me his old drawing tablet. I spent most of the ensuing week on the above digital painting.

I’d only colored anything a couple things at this point, all of them basically flood-filled. I hadn’t tried shading, backgrounds, textures, colored lines, perspective.

Naturally, I tried all of them at once. Some of these experiments were, er, more successful than others. (Along similar lines, this year, I animated something for the first time.)

Regardless of the outcome, I’d now done my best at all of these things at least once, and learned a lot about each of them.

I’m reminded of every introductory beginner guide to anything ever, which introduces one concept at a time and carefully shields you from anything you haven’t seen yet. Or stories of programming teachers who will actually chide a student for using something they haven’t been taught yet.

Fuck that noise. Dive in; keep trying things you’ve never tried before. It’s how babies learn a language, which I think is pretty impressive, given that they didn’t already know one. Parents don’t restrict their speech to single-word sentences until the baby has caught on, and then start introducing nouns. They talk normally. The baby marinates in the language and picks it up over time by playing with it, starting with whatever’s most accessible.

And hey, this works for adults too. I’m pretty sure being dropped in a country where no one speaks your native tongue will have you picking up a second language much more quickly than taking night classes and having artificial conversations about dinner dates. The only real advantage a baby has is a complete lack of obligations, so they’re free to sit and listen to people talk all day.

I figured another way to do the thing and dive in would be to finally draw my own avatar.

This took a few attempts.

The first two were in March, and I used the first one for a while. 3 through 5 were all done in June in an attempt to replace the first one with something better, but all went unused. Number 6 was the first real success, lasting through the end of the year with a few seasonal variations. 7 was an attempt to update it earlier this year, and the last one is only a few weeks old and is my current avatar.

Some of these are really bad, but I can look at them and tell exactly what I was trying to do.

-

I didn’t even draw this; I made it with vectors, using the mouse, because I couldn’t draw well enough to make it otherwise.

-

Drawn by hand with a tablet.

-

The angle worked out really poorly last time, so I tried working around that by aiming from straight ahead. The ears are no longer solid blobs. There are eyebrows! The nose is shaped more like a nose. The previous colors kinda clashed, so this is more reddish overall.

-

Straight-on didn’t work out and is hardly identifiable as anything, so back to angled. Still trying to work out pupils. Right ear is drawn behind the bow, so it doesn’t look like the bow is holding it on. I don’t understand mouths, so I’ll cheat and do a smirk instead.

-

More angled, moved upwards to center the face. Shaded and colored the lines this time. Still trying to work out pupils. Around this time I was trying to figure out how ears on the far side of the head work, and something catastrophic happened here. I was waffling on whether the insides of the ears should have one line or two, so I tried compromising with one line plus a shadow. Bow has a bit of ribbon sticking out, as a hint that it’s tied on and not just glued there.

-

Made the lines much thicker, so they wouldn’t vanish when shrunk down. Kept the shapes simple for the same reason. Pupils reduced to dots, which actually works just fine. Fluff details are bigger, which helps cohesion. Background color matches the bow color, which helps tremendously. Mouth finally works by being aligned with the bottom of the nose. Shape of the muzzle protrusion is, finally, big enough.

-

More detailed bow shape. Bow is now clearly tied to the ear. Insides of ears are rendered again. Entire mouth line is shown. Some shading is present again. Pupils have expanded, but not too much, and have a glint again. Lines are colored again.

-

Small fluff details made bigger again. Background is greener to avoid the clash from last time. Mouth is open and has the little corner crease. Lines rethickened. Dropped the shaded lines, since they didn’t work out last time, but kept the lines as mostly a single non-black color. Thickened the white double outline, which looked goofy in #6 when it was thinner than the regular outline.

In every case I was trying to improve on something that hadn’t gone well before. In every case I was trying to make the best avatar I had ever made. Sometimes that meant trying something I hadn’t tried before; sometimes that meant dropping something that hadn’t worked before; sometimes that meant resurrecting something and fiddling with it until it worked.

Always try to do the best work you’ve ever done. The key is that “best” is entirely subjective, and you can define it however you want! I was terrible at drawing digitigrade legs (like cats’ back legs) for the longest time, so for a while my definition of “best” was “has the best legs I’ve ever drawn”. Pick whatever axes you like. Vary them regularly, too — both to avoid burnout and to avoid concentrating on one thing over all else.

I had a high school teacher who liked to say that “practice makes perfect” is wrong; rather, “perfect practice makes perfect”. I don’t think that phrasing is any more illuminating, but I get his point: repeating exactly the same thing over and over will only make you better at that one thing. Incremental improvement is how you progress. (Hmm, I guess that’s not as catchy.)

There’s a catch to doing this effectively, which might as well be its own bolded quip.

Learn how to tell what’s wrong. This is a tricky muscle to exercise deliberately, but the better you get at it, the more (and more quickly) you can learn from your mistakes. Eventually you learn not to make them in the first place.

Are you a programmer? Spot the problems in this snippet of some C-like language:

1if (won = true)

2 print("You did it!");

3else

4 print("You failed!");

5 print("Press any key to try again.");

They probably stick out to you like a sore thumb. You’ve seen and made these basic mistakes so many times that your eye has learned to recoil from the very shape of them. You’re far less likely to make them now, because the moment you make the mistake, your brain vomits a little.

Unfortunately, this is something that only comes with experience, so you’ll just have to slog through making the baby mistakes. Asking for expert advice helps a little, but I think it mostly helps you find the mistake in the first place, so you can notice it again yourself next time. Spotting your own fuckups engraves them into your brain much more effectively than having them pointed out to you.

The one hack I can think of is to drown yourself in good work. The best you can find. If you get a sense for what good work is like, you might at least get the sense that something is off about your own, which is a first step to figuring out what the problem is.

You know how some people are “naturally” talented at a thing? It just “clicks” for them? I strongly suspect their actual natural talent is more about understanding their own mistakes in a particular kind of work, which lets them skip over a lot of the boring beginner part where you fumble around uselessly.

Know what’s possible. Every skill has its own toolbox, and part of learning the skill is learning what’s in the toolbox. Being familiar with image editing software has been hugely helpful for experimenting with art; for example, changing the color of your lines is trivial if you know how to use alpha lock. If you don’t know, will you even suspect it exists?

I recall a Doom Let’s Play with a conversation that went like this:

A: Ah, these textures are misaligned. It’s so easy to fix, too; you can just press A in Doom Builder to align everything across several walls.

B: Wait, really? I always do it manually.

A: What? Are you serious? So when you have a big curve made out of a lot of pieces—

B: That’s why I don’t make big curves out of a lot of pieces!

If you think something is impossible (or at least impractical), you cut yourself off from whole areas of experimentation.

Listen to more experienced people when they talk about how they work. Poke around your tools and see what all the buttons do. Come up with your own tricks — it sure worked for Bob Ross.

What does this have to do with pixel art? Not much. Pixel art relates to a rough converse of this, which is that sometimes, it’s nice to limit what’s possible. I’d never really given pixel art a try until I made these last month, and it turned out to be a really fun medium. With the drastically lower resolution and a pre-chosen fixed palette (made by someone else), I was forced to forget about how smooth my curves are or how to pick colors that work well together. Instead, I was free to play with the effects different colors have on each other, experiment with light and shading in a very simple way, and add in small details that I’d usually not think about.

Similarly, I’m now trying out the PICO-8 “fantasy console”, a tiny virtual video game system with some fairly severe restrictions. As a result, after a couple days of effort, I’m much closer to having a (graphical!) video game written than I ever have been before. I’m capable of making my own sprites now, and there can’t be too many of them anyway. Even the music editor is simple enough that I can make a passable tune. If I’d tried to make a little platformer in some massively-powerful general-purpose game engine, I’d have drowned in all the resources and code I’d need to find or create. Which has happened before. Probably more than once.

A blank canvas can be overwhelming sometimes; infinite possibilities are a lot to sift through. Cutting down on those options is freeing in its own way.

Step back and acknowledge your progress.

Learning a thing is frustrating sometimes. A lot of the time, even. Progress is slow and incremental, and on any given day, you won’t feel any better than you were the previous day.

Keep your old stuff around. Look at it from time to time so you can actually see how far you’ve come.

I drew these one year apart. I’m still not great — I immediately see half a dozen things in the more recent version that make me wince. But I’m better.

I think this is the most recent thing I’ve finished. It’s certainly a far cry from some pencil scribbles.

I hope I can get much better at this. Expressing ideas visually feels like a superpower — I can take vague images in my head and inject them directly into other people’s eyeballs. It keeps turning out to be useful, too: I’ve drawn myself avatars and banners, I drew the header for this site, I can draw sprites and illustrations for my own little games. It even taught me a few things that turned out to be useful for level design.

So, learn a lot of things. Try radically new things from time to time. Write a poem, bake a cake, make a video game. You’ll have experienced making something new, and you never know when that experience might come in handy. Doing rudimentary web design turned out to give me a head start at understanding color; who would’ve guessed?

I’m only writing this post now because I just realized that I hit a breakthrough point. I don’t really know how to explain it precisely in terms of art, so let me try language instead.

A very frustrating stage of learning a new (spoken) language is the late-beginner stage. You know the basic grammar and understand how the language is generally put together; you just don’t know many words. Learning resources are starting to dry up — everything’s always written for complete beginners — but you struggle to transition to learning from real native media, because you have to stop to look up every other word.

If you stick with it, you’ll eventually claw your way up to a kind of critical mass, where you know enough vocabulary that you can start to pick up the rest from context. You no longer need to spend ten minutes fishing through a dictionary just to understand what someone is talking about, and can instead focus on picking up nuance and idioms and more complex grammar. From there, you can accelerate.

I sense I’ve hit a similar kind of critical mass with drawing. I spent a long time fighting just to get my hand to draw the shapes I wanted, which got in the way of learning what shapes I should want in the first place. I realized only days ago that I don’t have this problem nearly so much any more.

That means I can now experiment with different kinds of shapes! It means I can play with line thickness and rely less on undo, because I don’t have to worry that I won’t be able to redraw a line. It means I can try painting more instead of always having a separate lineart layer. I can try more stuff without struggling with the basics.

It took a while to get here, but it’s paying off, and it’s been pretty cool to watch happen.

![[process]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-process.png)