I’m almost 30, so I have to start practicing being crotchety.

Okay, maybe not all video games, but something curious has definitely happened here. Please bear with me for a moment.

Discovering Doom

Surprise! This is about Doom again.

Last month, I sat down and played through the first episode of Doom 1 for the first time. Yep, the first time. I’ve mentioned before that I was introduced to Doom a bit late, and mostly via Doom 2. I’m familiar with a decent bit of Doom 1, but I’d never gotten around to actually playing through any of it.

I might be almost unique in playing Doom 1 for the first time decades after it came out, while already being familiar with the series overall. I didn’t experience Doom 1 only in contrast to modern games, but in contrast to later games using the same engine.

It was very interesting to experience Romero’s design sense in one big chunk, rather than sprinkled around as it is in Doom 2. Come to think of it, Doom 1’s first episode is the only contiguous block of official Doom maps to have any serious consistency: it sticks to a single dominant theme and expands gradually in complexity as you play through it. Episodes 2 and 3, as well of most of Doom 2, are dominated by Sandy Petersen’s more haphazard and bizarre style. Episode 4 and Final Doom, if you care to count them, are effectively just map packs.

It was also painfully obvious just how new this kind of game was. I’ve heard Romero stress the importance of contrast in floor height (among other things) so many times, and yet Doom 1 is almost comically flat. There’s the occasional lift or staircase, sure, but the spaces generally feel like they’re focused around a single floor height with the occasional variation. Remember, floor height was a new thing — id had just finished making Wolfenstein 3D, where the floor and ceiling were completely flat and untextured.

The game was also clearly designed for people who had never played this kind of game. There was much more ammo than I could possibly carry; I left multiple shell boxes behind on every map. The levels were almost comically easy, even on UV, and I’m not particularly good at shooters. It was a very stark contrast to when I played partway through The Plutonia Experiment a few years ago and had to rely heavily on quicksaving.

Seeing Doom 1 from a Doom 2 perspective got me thinking about how design sensibilities in shooters have morphed over time. And then I realized something: I haven’t enjoyed an FPS since Quake 2.

Or… hang on. That’s not true. I enjoy Splatoon (except when I lose). I loved the Metroid Prime series. I played Team Fortress 2 for quite a while.

On the other hand, I found Half-Life 2 a little boring, I lost interest in Doom 3 before even reaching Hell, and I bailed on Quake 4 right around the extremely hammy spoiler plot thing. I loved Fallout, but I couldn’t stand Fallout 3. Uncharted is pretty to watch, but looks incredibly tedious to play. I never cared about Halo. I don’t understand the appeal of Counterstrike or Call of Duty.

If I made a collage of screenshots of these two sets of games, you’d probably spot the pattern pretty quickly. It seems I can’t stand games with realistic graphics.

I have a theory about this.

The rise of realism

Quake introduced the world to “true” 3D — an environment made out of arbitrary shapes, not just floors and walls. (I’m sure there were other true-3D games before it, but I challenge you to name one off the top of your head.)

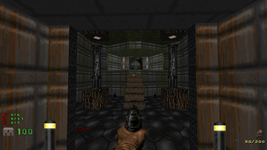

Before Quake, games couldn’t even simulate a two-story building, which ruled out most realistic architecture. Walls that slid sideways were virtually unique to Hexen (and, for some reason, the much earlier Wolfenstein 3D). So level designers built slightly more abstract spaces instead. Consider this iconic room from the very beginning of Doom’s E1M1.

What is this room? This is supposed to be a base of some kind, but who would build this room just to store a single armored vest? Up a flight of stairs, on a dedicated platform, and framed by glowing pillars? This is completely ridiculous.

But nobody thinks like that, and even the people who do, don’t really care too much. It’s a room with a clear design idea and a clear gameplay purpose: to house the green armor. It doesn’t matter that this would never be a real part of a base. The game exists in its own universe, and it establishes early on that these are the rules of that universe. Sometimes a fancy room exists just to give the player a thing.

At the same time, the room still resembles a base. I can take for granted, in the back of my head, that someone deliberately placed this armor here for storage. It’s off the critical path, too, so it doesn’t quite feel like it was left specifically for me to pick up. The world is designed for the player, but it doesn’t feel that way — the environment implies, however vaguely, that other stuff is going on here.

Fast forward twenty years. Graphics and physics technology have vastly improved, to the point that we can now roughly approximate a realistic aesthetic in real-time. A great many games thus strive to do exactly that.

And that… seems like a shame. The better a game emulates reality, the less of a style it has. I can’t even tell Call of Duty and Battlefield apart.

That’s fine, though, right? It’s just an aesthetic thing. It doesn’t really affect the game.

It totally affects the game

Everything looks the same

“Realism” generally means “ludicrous amounts of detail” — even moreso if the environments are already partially-destroyed, which is a fairly common trope I’ll touch on again.

When everything is highly-detailed, screenshots may look very good, but gameplay suffers because the player can no longer tell what’s important. The tendency for everything to have a thick coating of sepia certainly doesn’t help.

Look at that Call of Duty screenshot again. What in this screenshot is actually important? What here matters to you as a player? As far as I can tell, the only critical objects are:

- Your current weapon

That’s it. The rocks and grass and billboards and vehicles and Hollywood sign might look very nice (by which I mean, “look like those things look”), but they aren’t important to the game at all. This might as well be a completely empty hallway.

To be fair, I haven’t played the game, so for all I know there’s a compelling reason to collect traffic cones. Otherwise, this screenshot is 100% noise. Everything in it serves only to emphasize that you’re in a realistic environment.

Don’t get me wrong, setting the scene is important, but something has been missed here. Detail catches the eye, and this screenshot is nothing but detail. None of it is relevant. If there were ammo lying around, would you even be able to find it?

Ah, but then, modern realistic games either do away with ammo pickups entirely or make them glow so you can tell they’re there. You know, for the realism.

(Speaking of glowing: something I always found ridiculous was how utterly bland the imp fireballs look in Doom 3 and 4. We have these amazing lighting engines, and the best we can do for a fireball is a solid pale orange circle? How do modern fireballs look less interesting than a Doom 1 fireball sprite?)

Even Fallout 2 bugged me a little with this; the world was full of shelves and containers, but it seemed almost all of them were completely empty. Fallout 1 had tons of loot waiting to be swiped from shelves, but someone must’ve decided that was a little silly and cut down on it in Fallout 2. So then, what’s the point of having so many shelves? They encourage the player to explore, then offer no reward whatsoever most of the time.

Environments are boring and static

Fallout 3 went right off the rails, filling the world with tons of (gray) detail, none of which I could interact with. I was barely finished with the first settlement before I gave up on the game because of how empty it felt. Everywhere was detailed as though it were equally important, but most of it was static decorations. From what I’ve seen, Fallout 4 is even worse.

Our graphical capabilities have improved much faster than our ability to actually simulate all the junk we’re putting on the screen. Hey, there’s a car! Can I get in it? Can I drive it? No, I can only bump into an awkwardly-shaped collision box drawn around it. So what’s the point of having a car, an object that — in the real world — I’m accustomed to being able to use?

And yet… a game that has nothing to do with driving a car doesn’t need you to be able to drive a car. Games are games, not perfect simulations of reality. They have rules, a goal, and a set of things the player is able to do. There’s no reason to make the player able to do everything if it has no bearing on what the game’s about.

This puts “realistic” games in an awkward position. How do they solve it?

One good example that comes to mind is Portal, which was rendered realistically, but managed to develop a style from the limited palette it used in the actual play areas. It didn’t matter that you couldn’t interact with the world in any way other than portaling walls and lifting cubes, because for the vast majority of the game, you only encountered walls and cubes! Even the “behind the scenes” parts at the end were mostly architecture, not objects, and I’m not particularly bothered that I can’t interact with a large rusty pipe.

The standouts were the handful of offices you managed to finagle your way into, which were of course full of files and computers and other desktop detritus. Everything in an office is — necessarily! — something a human can meaningfully interact with, but the most you can do in Portal is drop a coffee cup on the floor. It’s all the more infuriating if you consider that the plot might have been explained by the information in those files or on those computers. Portal 2 was in fact a little worse about this, as you spent much more time outside of the controlled test areas.

I think Left 4 Dead may have also avoided this problem by forcing the players to be moving constantly — you don’t notice that you can’t get in a car if you’re running for your life. The only time the players can really rest is in a safe house, which are generally full of objects the players can pick up and use.

Progression feels linear and prescripted

Portal dodged a huge bullet by not trying to emulate real-world environments, instead setting the player in deliberately-constructed test chambers. Games like Half-Life 2, which takes place in a realistic city, have a problem on their hands: realistic manmade spaces are designed for efficiency and utility, not interesting exploration. A very common trick is to just have the world be partially-destroyed. Apartment buildings are not terribly exciting to explore, so let’s jam half the doors and put a few upturned cars in the street.

This sucks. The design serves the realistic aesthetic, not the player’s experience, and has to be awkwardly contorted to fit into the game. The thing I love about Doom’s “abstract” design is that it can serve the gameplay first and be fit to aesthetics second. Metroid Prime did an excellent job of this as well, and I’d even call its design abstract — it has a lot more detail than Doom, sure, but the rooms are more like handwaved concepts than slices of a space that would reasonably exist. (Who would fill a cave with powered doors, anyway? Who cares?)

But returning to Portal, its main draw is one of my favorite properties of games: you could manipulate the environment itself. It’s the whole point of the game, even. And it seems to be conspicuously missing from many modern “realistic” games, partly because real environments are just static, but also in large part because… of the graphics!

Rendering a very complex scene is hard, so modern map formats do a whole lot of computing stuff ahead of time. (For similar reasons, albeit more primitive ones, vanilla Doom can’t move walls sideways.) Having any of the environment actually move or change is thus harder, so it tends to be reserved for fancy cutscenes when you press the button that lets you progress. And because grandiose environmental changes aren’t very realistic, that button often just opens a door or blows something up.

It feels hamfisted, like someone carefully set it all up just for me. Obviously someone did, but the last thing I want is to be reminded of that. I’m reminded very strongly of Half-Life 2, which felt like one very long corridor punctuated by the occasional overt physics puzzle. Contrast with Doom, where there are buttons all over the place and they just do things without drawing any particular attention to the results. Mystery switches are sometimes a problem, but for better or worse, Doom’s switches always feel like something I’m doing to the game, rather than the game waiting for me to come along so it can do some preordained song and dance.

I miss switches. Real switches, not touchscreens. Big chunky switches that take up half a wall.

It’s not just the switches, though. Several of Romero’s maps from episode 1 are shaped like a “horseshoe”, which more or less means that you can see the exit from the beginning (across some open plaza). More importantly, the enemies at the exit can see you, and will be shooting at you for much of the level.

That gives you choices, even within the limited vocabulary of Doom. Do you risk wasting ammo trying to take them out from a distance, or do you just dodge their shots all throughout the level? It’s up to you! You get to decide how to play the game, naturally, without choosing from a How Do You Want To Play The Game menu. Hell, Doom has entire speedrun categories focused around combat — Tyson for only using the fist and pistol, pacifist for never attacking a monster at all.

You don’t see a lot of that any more. Rendering an entire large area in a polygon-obsessed game is, of course, probably not going to happen — whereas the Doom engine can handle it just fine. I’ll also hazard a guess and say that having too much enemy AI going at once and/or rendering too many highly-detailed enemies at once is too intensive. Or perhaps balancing and testing multiple paths is too complicated.

Or it might be the same tendency I see in modding scenes: the instinct to obsessively control the player’s experience, to come up with a perfectly-crafted gameplay concept and then force the player to go through it exactly as it was conceived. Even Doom 4, from what I can see, has a shocking amount of “oh no the doors are locked, kill all the monsters to unlock them!” nonsense. Why do you feel the need to force the player to shoot the monsters? Isn’t that the whole point of the game? Either the player wants to do it and the railroading is pointless, or the player doesn’t want to do it and you’re making the game actively worse for them!

Something that struck me in Doom’s E1M7 was that, at a certain point, you run back across half the level and there are just straggler monsters all over the place. They all came out of closets when you picked up something, of course, but they also milled around while waiting for you to find them. They weren’t carefully scripted to teleport around you in a fixed pattern when you showed up; they were allowed to behave however they want, following the rules of the game.

Whatever the cause, something has been lost. The entire point of games is that they’re an interactive medium — the player has some input, too.

Exploration is discouraged

I haven’t played through too many recent single-player shooters, but I get the feeling that branching paths (true nonlinearity) and sprawling secrets have become less popular too. I’ve seen a good few people specifically praise Doom 4 for having them, so I assume the status quo is to… not.

That’s particularly sad off the back of Doom episode 1, which has sprawling secrets that often feel like an entire hidden part of the base. In several levels, merely getting outside qualifies as a secret. There are secrets within secrets. There are locked doors inside secrets. It’s great.

And these are real secrets, not three hidden coins in a level and you need to find so many of them to unlock more levels. The rewards are heaps of resources, not a fixed list of easter eggs to collect. Sometimes they’re not telegraphed at all; sometimes you need to do something strange to open them. Doom has a secret you open by walking up to one of two pillars with a heart on it. Doom 2 has a secret you open by run-jumping onto a light fixture, and another you open by “using” a torch and shooting some eyes in the wall.

I miss these, too. Finding one can be a serious advantage, and you can feel genuinely clever for figuring them out, yet at the same time you’re not permanently missing out on anything if you don’t find them all.

I can imagine why these might not be so common any more. If decorating an area is expensive and complicated, you’re not going to want to build large areas off the critical path. In Doom, though, you can make a little closet containing a powerup in about twenty seconds.

More crucially, many of the Doom secrets require the player to notice a detail that’s out of place — and that’s much easier to set up in a simple world like Doom. In a realistic world where every square inch is filled with clutter, how could anyone possibly notice a detail out of place? How can a designer lay any subtle hints at all, when even the core gameplay elements have to glow for anyone to pick them out from background noise?

This might be the biggest drawback to extreme detail: it ultimately teaches the player to ignore the detail, because very little of it is ever worth exploring. After running into enough invisible walls, you’re going to give up on straying from the beaten path.

We wind up with a world where players are trained to look for whatever glows, and completely ignore everything else. At which point… why are we even bothering?

There are no surprises

“Realistic” graphics tend to come along with a “realistic” world, and let’s face it, the real world can be a little dull. That’s why we invented video games, right?

Doom has a very clear design vocabulary. Here are some demons. They throw stuff at you; don’t get hit by it. Here are some guns, which you can all hold at once, because those are the rules. Also here’s a glowing floating sphere that gives you a lot of health.

What is a megasphere, anyway? Does it matter? It’s a thing in the game with very clearly-defined rules. It’s good; pick it up.

You can’t do that in a “realistic” game. (Or maybe you can, but we seem to be trying to avoid it.) You can’t just pick up a pair of stereoscopic glasses to inexplicably get night vision for 30 seconds; you need to have some night-vision goggles with batteries and it’s a whole thing. You can’t pick up health kits that heal you; you have to be wearing regenerative power armor and pick up energy cells. You can’t carry eight different weapons; you have to constantly switch between two. Even Doom 4 seems to be uncomfortable leaving brightly flashing keycards lying around — instead you retrieve them from the corpses of people wearing correspondingly-colored armor.

Everything needs an explanation, which vastly reduces the chances of finding anything too surprising or new.

I’m told that Call of Duty is the most popular vidya among the millenials, so I went to look at its weapons:

- Gun

- Fast gun

- Long gun

- Different gun

How exciting! If you click through each of those gun categories, you can even see the list of unintelligible gun model numbers, which are exactly what gets me excited about a game.

I wonder if those model numbers are real or not. I’m not sure which would be worse.

Get off my lawn

So my problem is that striving for realism is incredibly boring and counter-productive. I don’t even understand the appeal; if I wanted reality, I could look out my window.

“Realism” actively sabotages games. I can judge Doom or Mario or Metroid or whatever as independent universes with their own rules, because that’s what they are. A game that’s trying to mirror reality, I can only compare to reality — and it’ll be a very pale imitation.

It comes down to internal consistency. Doom and Team Fortress 2 and Portal and Splatoon and whatever else are pretty upfront about what they’re offering: you have a gun, you can shoot it, also you can run around and maybe press some buttons if you’re lucky. That’s exactly what you get. It’s right there on the box, even.

Then I load Fallout 3, and it tries to look like the real world, and it does a big song and dance asking me for my stats “in-world”, and it tries to imply I can roam this world and do anything I want and forge my own destiny. Then I get into the game, and it turns out I can pretty much just shoot, pick from dialogue trees, and make the occasional hamfisted moral choice. The gameplay doesn’t live up to what the environment tried to promise. The controls don’t even live up to what the environment tried to promise.

The great irony is that “realism” is harshly limiting, even as it grows ever more expensive and elaborate. I’m reminded of the Fat Man in Fallout 3, the gun that launches “mini nukes”. If that weapon had been in Fallout 1 or 2, I probably wouldn’t think twice about it. But in the attempted “realistic” world of Fallout 3, I have to judge it as though it were trying to be a real thing — because it is! — and that makes it sound completely ridiculous.

(It may sound like I’m picking on Fallout 3 a lot here, but to its credit, it actually had enough stuff going on that it stands out to me. I barely remember anything about Doom 3 or Quake 4, and when I think of Half-Life 2 I mostly imagine indistinct crumbling hallways or a grungy river that never ends.)

I’ve never felt this way about series that ignored realism and went for their own art style. Pikmin 3 looks very nice, but I never once felt that I ought to be able to do anything other than direct Pikmin around. Metroid Prime looks great too and has some “realistic” touches, but it still has a very distinct aesthetic, and it manages to do everything important with a relatively small vocabulary — even plentiful secrets.

I just don’t understand the game industry (and game culture)’s fanatical obsession with realistic graphics. They make games worse. It’s entirely possible to have an art style other than “get a lot of unpaid interns to model photos of rocks”, even for a mind-numbingly bland army man simulator. Please feel free to experiment a little more. I would love to see more weird and abstract worlds that follow their own rules and drag you down the rabbit hole with them.

![[articles]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-articles.png)