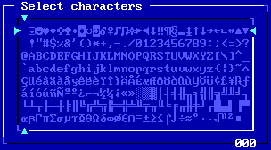

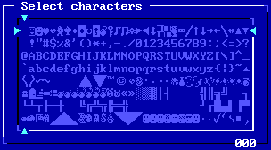

In the beginning, there was ZZT. ZZT was a set of little shareware games for DOS that used VGA text mode for all the graphics, leading to such whimsical Rogue-like choices as ä for ammo pickups, Ω for lions, and ♀ for keys. It also came with an editor, including a small programming language for creating totally custom objects, which gave it the status of “game creation system” and a legacy that survives even today.

A little later on, there was MegaZeux. MegaZeux was something of a spiritual successor to ZZT, created by (as I understand it) someone well-known for her creative abuse of ZZT’s limitations. It added quite a few bells and whistles, most significantly a built-in font editor, which let aspiring developers draw simple sprites rather than rely on whatever they could scrounge from the DOS font.

And then…

And then, nothing. MegaZeux was updated for quite a while, and (unlike ZZT) has even been ported to SDL so it can actually run on modern operating systems. But there was never a third entry in this series, another engine worthy of calling these its predecessors.

I think that’s a shame.

The legacy

Plenty of people have never heard of ZZT, and far more have never heard of MegaZeux, so here’s a brief primer.

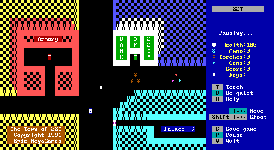

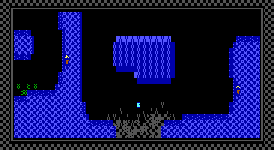

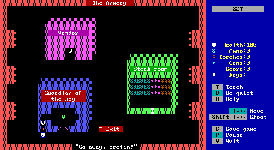

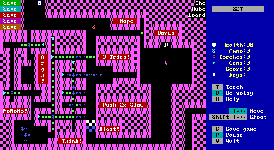

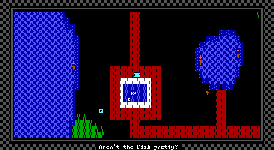

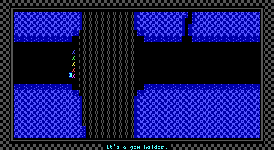

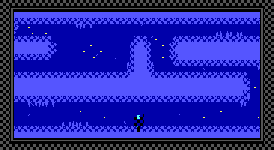

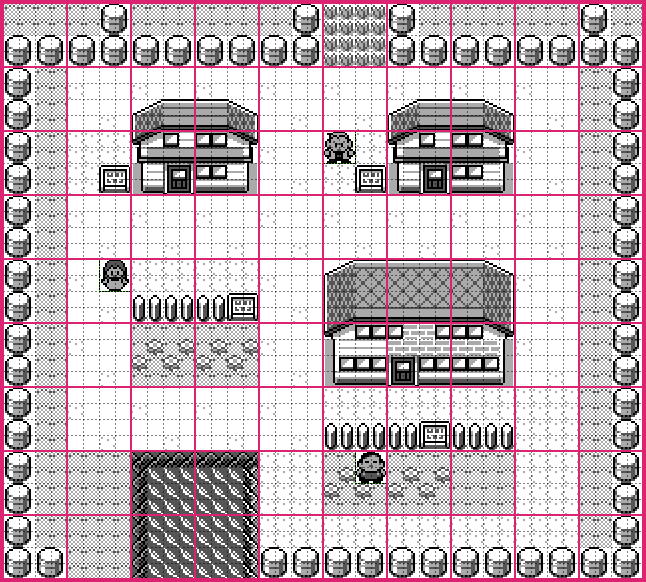

Both were released as “first-episode” shareware: they came with one game free, and you could pony up some cash to get the sequels. Those first games — Town of ZZT and Caverns of Zeux — have these moderately iconic opening scenes.

In the intervening decades, all of the sequels have been released online for free. If you want to try them yourself, ZZT 3.2 includes Town of ZZT and its sequels (but must be run in DOSBox), and you can get MegaZeux 2.84c, Caverns of Zeux, and the rest of the Zeux series separately.

Town of ZZT has you, the anonymous player, wandering around a loosely-themed “town” in search of five purple keys. It’s very much a game of its time: the setting is very vague but manages to stay distinct and memorable with very light touches; the puzzles range from trivial to downright cruel; the interface itself fights against you, as you can’t carry more than one purple key at a time; and the game can be softlocked in numerous ways, only some of which have advance warning in the form of “SAVE!!!” written carved directly into the environment.

Caverns of Zeux is a little more cohesive, with a (thin) plot that unfolds as you progress through the game. Your objectives are slightly vaguer; you start out only knowing you’re trapped in a cave, and further information must be gleaned from NPCs. The gameplay is shaken up a couple times throughout — you discover spellbooks that give you new abilities, but later lose your primary weapon. The meat of the game is more about exploring and less about wacky Sokoban puzzles, though with many of the areas looking very similar and at least eight different-colored doors scattered throughout the game, the backtracking can get frustrating.

Those are obviously a bit retro-looking now, but they’re not bad for VGA text made by individual hobbyists in 1991 and 1994. ZZT only even uses CGA’s eight bright colors. MegaZeux takes a bit more advantage of VGA capabilities to let you edit the palette as well as the font, but games are still restricted to only using 16 colors at one time.

That's great, but who cares?

A fair question!

ZZT and MegaZeux both occupy a unique game development niche. It’s the same niche as (Z)Doom, I think, and a niche that very few other tools fill.

I’ve mumbled about this on Twitter a couple times, and several people have suggested that the PICO-8 or Mario Maker might be in the same vein. I disagree wholeheartedly! ZZT, MegaZeux, and ZDoom all have two critical — and rare — things in common.

-

You can crack open the editor, draw a box, and have a game. On the PICO-8, you are a lonely god in an empty void; you must invent physics from scratch before you can do anything else. ZZT, MegaZeux, and Doom all have enough built-in gameplay to make a variety of interesting levels right out of the gate. You can treat them as nothing more than level editors, and you’ll be hitting the ground running — no code required. And unlike most “no programming” GCSes, I mean that literally!

-

If and when you get tired of only using the built-in objects, you can extend the engine. ZZT and MegaZeux have programmable actors built right in. Even vanilla Doom was popular enough to gain a third-party tool, DEHACKED, which could edit the compiled

doom.exeto customize actor behavior. Mario Maker might be a nice and accessible environment for making games, but at the end of the day, the only thing you can make with it is Mario.

Both of these properties together make for a very smooth learning curve. You can open the editor and immediately make something, rather than needing to absorb a massive pile of upfront stuff before you can even get a sprite on the screen. Once you need to make small tweaks, you can dip your toes into robots — a custom pickup that gives you two keys at once is four lines of fairly self-explanatory code. Want an NPC with a dialogue tree? That’s a little more complex, but not much. And then suddenly you discover you’re doing programming. At the same time, you get rendering, movement, combat, collision, health, death, pickups, map transitions, menus, dialogs, saving/loading… all for free.

MegaZeux has one more nice property, the art learning curve. The built-in font is perfectly usable, but a world built from monochrome 8×14 tiles is a very comfortable place to dabble in sprite editing. You can add eyebrows to the built-in player character or slightly reshape keys to fit your own tastes, and the result will still fit the “art style” of the built-in assets. Want to try making your own sprites from scratch? Go ahead! It’s much easier to make something that looks nice when you don’t have to worry about color or line weight or proportions or any of that stuff.

It’s true that we’re in an “indie” “boom” right now, and more game-making tools are available than ever before. A determined game developer can already choose from among dozens (hundreds?) of editors and engines and frameworks and toolkits and whatnot. But the operative word there is “determined“. Not everyone has their heart set on this. The vast majority of people aren’t interested in devoting themselves to making games, so the most they’d want to do (at first) is dabble.

But programming is a strange and complex art, where dabbling can be surprisingly difficult. If you want to try out art or writing or music or cooking or dance or whatever, you can usually get started with some very simple tools and a one-word Google search. If you want to try out game development, it usually requires programming, which in turn requires a mountain of upfront context and tool choices and explanations and mysterious incantations and forty-minute YouTube videos of some guy droning on in monotone.

To me, the magic of MegaZeux is that anyone with five minutes to spare can sit down, plop some objects around, and have made a thing.

Deep dive

MegaZeux has a lot of hidden features. It also has a lot of glass walls. Is that a phrase? It should be a phrase. I mean that it’s easy to find yourself wanting to do something that seems common and obvious, yet find out quite abruptly that it’s structurally impossible.

I’m not leading towards a conclusion here, only thinking out loud. I want to explain what makes MegaZeux interesting, but also explain what makes MegaZeux limiting, but also speculate on what might improve on it. So, you know, something for everyone.

Big picture

MegaZeux is a top-down adventure-ish game engine. You can make platformers, if you fake your own gravity; you can make RPGs, if you want to build all the UI that implies.

MegaZeux games can only be played in, well, MegaZeux. Games that need instructions and multiple downloads to be played are fighting an uphill battle. It’s a simple engine that seems reasonable to deploy to the web, and I’ve heard of a couple attempts at either reimplementing the engine in JavaScript or throwing the whole shebang at emscripten, but none are yet viable.

People have somewhat higher expectations from both games and tools nowadays. But approachability is often at odds with flexibility. The more things you explicitly support, the more complicated and intimidating the interface — or the more hidden features you have to scour the manual to even find out about.

I’ve looked through the advertising screenshots of Game Maker and RPG Maker, and I’m amazed how many things are all over the place at any given time. It’s like trying to configure the old Mozilla Suite. Every new feature means a new checkbox somewhere, and eventually half of what new authors need to remember is the set of things they can safely ignore.

SLADE’s Doom map editor manages to be much simpler, but I’m not particularly happy with that, either — it’s not clever enough to save you from your mistakes (or necessarily detect them), and a lot of the jargon makes no sense unless you’ve already learned what it means somewhere else. Plus, making the most of ZDoom’s extra features tends to involve navigating ten different text files that all have different syntax and different rules.

MegaZeux has your world, some menus with objects in them, and spacebar to place something. The UI is still very DOS-era, but once you get past that, it’s pretty easy to build something.

How do you preserve that in something “modern”? I’m not sure. The only remotely-similar thing I can think of is Mario Maker, which cleverly hides a lot of customization options right in the world editor UI: placing wings on existing objects, dropping objects into blocks, feeding mushrooms to enemies to make them bigger. The downside is that Mario Maker has quite a lot of apocryphal knowledge that isn’t written down anywhere. (That’s not entirely a downside… but I could write a whole other post just exploring that one sentence.)

Graphics

Oh, no.

Graphics don’t make the game, but they’re a significant limiting factor for MegaZeux. Fixing everything to a grid means that even a projectile can only move one tile at a time. Only one character can be drawn per grid space, so objects can’t usefully be drawn on top of each other. Animations are difficult, since they eat into your 255-character budget, which limits real-time visual feedback. Most individual objects are a single tile — creating anything larger requires either a lot of manual work to keep all the parts together, or the use of multi-tile sprites which don’t quite exist on the board.

And yet! The same factors are what make MegaZeux very accessible. The tiles are small and simple enough that different art styles don’t really clash. Using a grid means simple games don’t have to think about collision detection at all. A monochromatic font can be palette-shifted, giving you colorful variants of the same objects for free.

How could you scale up the graphics but preserve the charm and approachability? Hmm.

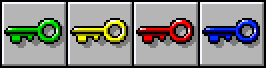

I think the palette restrictions might be important here, but merely bumping from 2 to 8 colors isn’t quite right. The palette-shifting in MegaZeux always makes me think of keys first, and multi-colored keys make me think of Chip’s Challenge, where the key sprites were simple but lightly shaded.

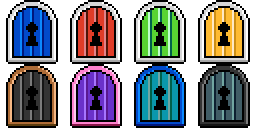

The game has to contain all four sprites separately. If you wanted to have a single sprite and get all of those keys by drawing it in different colors, you’d have to specify three colors per key: the base color, a lighter color, and a darker color. In other words, a ramp — a short gradient, chosen from a palette, that can represent the same color under different lighting. Here are some PICO-8 ramps, for example. What about a sprite system that drew sprites in terms of ramps rather than individual colors?

I whipped up this crappy example to illustrate. All of the doors are fundamentally the same image, and all of them use only eight colors: black, transparent, and two ramps of three colors each. The top-left door could be expressed as just “light gray” and “blue” — those colors would be expanded into ramps automatically, and black would remain black.

I don’t know how well this would work, but I’d love to see someone try it. It may not even be necessary to require all sprites be expressed this way — maybe you could import your own truecolor art if you wanted. ZDoom works kind of this way, though it’s more of a historical accident: it does support arbitrary PNGs, but vanilla Doom sprites use a custom format that’s in terms of a single global palette, and only that custom format can be subjected to palette manipulation.

Now, MegaZeux has the problem that small sprites make it difficult to draw bigger things like UI (or a non-microscopic player). The above sprites are 32×32 (scaled up 2× for ease of viewing here), which creates the opposite problem: you can’t possibly draw text or other smaller details with them.

I wonder what could be done here. I know that the original Pokémon games have a concept of “metatiles”: every map is defined in terms of 4×4 blocks of smaller tiles. You can see it pretty clearly on this map of Pallet Town. Each larger square is a metatile, and many of them repeat, even in areas that otherwise seem different.

I left the NPCs in because they highlight one of the things I found most surprising about this scheme. All the objects you interact with — NPCs, signs, doors, items, cuttable trees, even the player yourself — are 16×16 sprites. The map appears to be made out of 16×16 sprites, as well — but it’s really built from 8×8 tiles arranged into bigger 32×32 tiles.

This isn’t a particularly nice thing to expose directly to authors nowadays, but it demonstrates that there are other ways to compose tiles besides the obvious. Perhaps simple terrain like grass and dirt could be single large tiles, but you could also make a large tile by packing together several smaller tiles?

Text? Oh, text can just be a font.

Player status

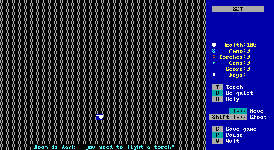

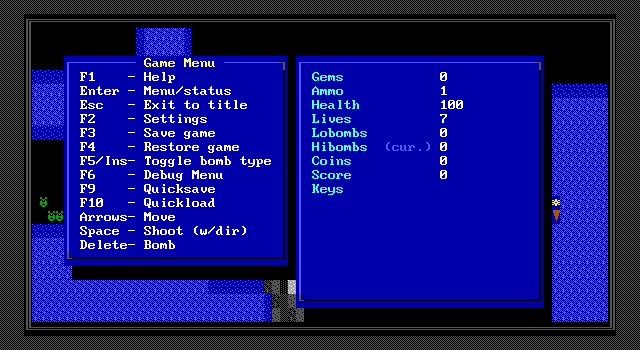

MegaZeux has no HUD. To know how much health you have, you need to press Enter to bring up the pause menu, where your health is listed in a stack of other numbers like “gems” and “coins”. I say “menu”, but the pause menu is really a list of keyboard shortcuts, not something you can scroll through and choose items from.

To be fair, ZZT does reserve the right side of the screen for your stats, and it puts health at the top. I find myself scanning the MegaZeux pause menu for health every time, which seems a somewhat poor choice for the number that makes the game end when you run out of it.

Unlike most adventure games, your health is an integer starting at 100, not a small number of hearts or whatever. The only feedback when you take damage is a sound effect and an “Ouch!” at the bottom of the screen; you don’t flinch, recoil, or blink. Health pickups might give you any amount of health, you can pick up health beyond 100, and nothing on the screen tells you how much you got when you pick one up. Keeping track of your health in your head is, ah, difficult.

MegaZeux also has a system of multiple lives, but those are also just a number, and the default behavior on “death” is for your health to reset to 100 and absolutely nothing else happens. Walking into lava (which hurts for 100 at a time) will thus kill you and strip you of all your lives quite rapidly.

It is possible to manually create a HUD in MegaZeux using the “overlay” layer, a layer that gets drawn on top of everything else in the world. The downside is that you then can’t use the overlay for anything in-world, like roofs or buildings that can be walked behind. The overlay can be in multiple modes, one that’s attached to the viewport (like a HUD) and one that’s attached to the world (like a ceiling layer), so an obvious first step would be offering these as separate features.

An alternative is to use sprites, blocks of tiles created and drawn as a single unit by Robotic code. Sprites can be attached to the viewport and can even be drawn even above the overlay, though they aren’t exposed in the editor and must be created entirely manually. Promising, if clumsy and a bit non-obvious — I only just now found out about this possibility by glancing at an obscure section of the manual.

Another looming problem is that text is the same size as everything else — but you generally want a HUD to be prominent enough to glance at very quickly.

This makes me wonder how more advanced drawing could work in general. Instead of writing code by hand to populate and redraw your UI, could you just drag and drop some obvious components (like “value of this number”) onto a layer? Reuse the same concept for custom dialogs and menus, perhaps?

Inventory

MegaZeux has no inventory. Or, okay, it has sort of an inventory, but it’s all over the place.

The stuff in the pause menu is kind of like an inventory. It counts ammo, gems, coins, two kinds of bombs, and a variety of keys for you. The game also has multiple built-in objects that can give you specific numbers of gems and coins, which is neat, except that gems and coins don’t do actually anything. I think they increase your score, but until now I’d forgotten that MegaZeux has a score.

A developer can also define six named “counters” (i.e., integers) that will show up on the pause menu when nonzero. Caverns of Zeux uses this to show you how many rainbow gems you’ve discovered… but it’s just a number labeled RainbowGems, and there’s no way to see which ones you have.

Other than that, you’re on your own. All of the original Zeux games made use of an inventory, so this is a really weird oversight. Caverns of Zeux also had spellbooks, but you could only see which ones you’d found by trying to use them and seeing if it failed. Chronos Stasis has maybe a dozen items you can collect and no way to see which ones you have — though, to be fair, you use most of them in the same place. Forest of Ruin has a fairly standard inventory, but no way to view it. All three games have at least one usable item that they just bind to a key, which you’d better remember, because it’s game-specific and thus not listed in the general help file.

To be fair, this is preposterously flexible in a way that a general inventory might not be. But it’s also tedious for game authors and potentially confusing for players.

I don’t think an inventory would be particularly difficult to support, and MegaZeux is already halfway there. Most likely, the support is missing because it would need to be based on some concept of a custom object, and MegaZeux doesn’t have that either. I’ll get to that in a bit.

Creating new objects

MegaZeux allows you to create “robots”, objects that are controlled entirely through code you write in a simple programming language. You can copy and paste robots around as easily as any other object on the map. Cool.

What’s less cool is that robots can’t share code — when you place one, you make a separate copy of all of its code. If you create a small horde of custom monsters, then later want to make a change, you’ll have to copy/paste all the existing ones. Hope you don’t have them on other boards!

Some workarounds exist: you could make use of robots’ ability to copy themselves at runtime, and it’s possible to save or load code to/from an external file at runtime. More cumbersome than defining a template object and dropping it wherever you want, and definitely much less accessible.

This is really, really bad, because the only way to extend any of the builtin objects is to replace them with robots!

I’m a little spoiled by ZDoom, where you can create as many kinds of actor as you want. Actors can even inherit from one another, though the mechanism is a little limited and… idiosyncratic, so I wouldn’t call it beginner-friendly. It’s pretty nice to be able to define a type of monster or decoration and drop it all over a map, and I’m surprised such a thing doesn’t exist in MegaZeux, where boards and the viewport both tend to be fairly large.

This is the core of how ZDoom’s inventory works, too. I believe that inventories contain only kinds, not individual actors — that is, you can have 5 red keys, but the game only knows “5 of RedCard” rather than having five distinct RedCard objects. I’m sure part of the reason MegaZeux has no general-purpose inventory is that every custom object is completely distinct, with nothing fundamentally linking even identical copies of the same robot together.

Combat

By default, the player can shoot bullets by holding Space and pressing a direction. (Moving and shooting at the same time is… difficult.) Like everything else, bullets are fixed to the character grid, so they move an entire tile at a time.

Bullets can also destroy other projectiles, sometimes. A bullet hitting another bullet will annihilate both. A bullet hitting a fireball might either turn the fireball into a regular fire tile or simple be destroyed, depending on which animation frame the fireball is in when the bullet hits it. I didn’t know this until someone told me only a couple weeks ago; I’d always just thought it was random and arbitrary and frustrating. Seekers can’t be destroyed at all.

Most enemies charge directly at you; most are killed in one hit; most attack you by colliding with you; most are also destroyed by the collision.

The (built-in) combat is fairly primitive. It gives you something to do, but it’s not particularly satisfting, which is unfortunate for an adventure game engine.

Several factors conspire here. Graphical limitations make it difficult to give much visual feedback when something (including the player) takes damage or is destroyed. The motion of small, fast-moving objects on a fixed grid can be hard to keep track of. No inventory means weapons aren’t objects, either, so custom weapons need to be implemented separately in the global robot. No custom objects means new enemies and projectiles are difficult to create. No visual feedback means hitscan weapons are implausible.

I imagine some new and interesting directions would make themselves obvious in an engine with a higher resolution and custom objects.

Robotic

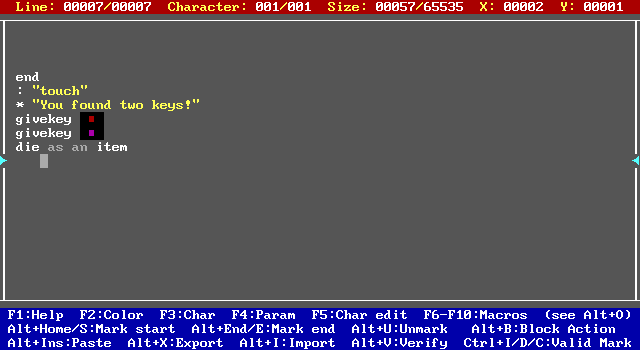

Robotic is MegaZeux’s programming language for defining the behavior of robots, and it’s one of the most interesting parts of the engine. A robot that acts like an item giving you two keys might look like this:

1end

2: "touch"

3* "You found two keys!"

4givekey c04

5givekey c05

6die as an item

Robotic has no blocks, loops, locals, or functions — though recent versions can fake functions by using special jumps. All you get is a fixed list of a few hundred commands. It’s effectively a form of bytecode assembly, with no manual assembling required.

And yet! For simple tasks, it works surprisingly well. Creating a state machine, as in the code above, is straightforward. end stops execution, since all robots start executing from their first line on start. : "touch" is a label (:"touch" is invalid syntax) — all external stimuli are received as jumps, and touch is a special label that a robot jumps to when the player pushes against it. * displays a message in the colorful status line at the bottom of the screen. givekey gives a key of a specific color — colors are a first-class argument type, complete with their own UI in the editor and an automatic preview of the particular colors. die as an item destroys the robot and simultaneously moves the player on top of it, as though the player had picked it up.

A couple other interesting quirks:

-

Most prepositions, articles, and other English glue words are semi-optional and shown in grey. The line

die as an itemabove hasas angreyed out, indicating that you could just typedie itemand MegaZeux would fill in the rest. You could also typedie as item,die an item, or evendie through item, because all ofas,an, andthroughact like whitespace. Most commands sprinkle a few of these in to make themselves read a little more like English and clarify the order of arguments. -

The same label may appear more than once. However, labels may be zapped, and a jump will always go to the first non-zapped occurrence of a label. This lets an author encode a robot’s state within the state of its own labels, obviating the need for state-tracking variables in many cases. (Zapping labels predates per-robot variables — “local counters” — which are unhelpfully named

localthroughlocal32.)Of course, this can rapidly spiral out of control when state changes are more complicated or several labels start out zapped or different labels are zapped out of step with each other. Robotic offers no way to query how many of a label have been zapped and MegaZeux has no debugger for label states, so it’s not hard to lose track of what’s going on. Still, it’s an interesting extension atop a simple label-based state machine.

-

The built-in types often have some very handy shortcuts. For example,

GO [dir] #tells a robot to move in some direction, some number of spaces. The directions you’d expect all work:NORTH,SOUTH,EAST,WEST, and synonyms likeNandUP. But there are some extras likeRANDNBto choose a random direction that doesn’t block the robot, orSEEKto move towards the player, orFLOWto continue moving in its current direction. Some of the extras only make sense in particular contexts, which complicates them a little, but the ability to tell an NPC to wander aimlessly with onlyRANDNBis incredible. -

Robotic is more powerful than you might expect; it can change anything you can change in the editor, emulate the behavior of most other builtins, and make use of several features not exposed in the editor at all.

Nowadays, the obvious choice for an embedded language is Lua. It’d be much more flexible, to be sure, but it’d lose a little of the charm. One of the advantages of creating a totally custom language for a game is that you can add syntax for very common engine-specific features, like colors; in a general-purpose language, those are a little clumsier.

1function myrobot:ontouch(toucher)

2 if not toucher.is_player then

3 return false

4 end

5 world:showstatus("You found two keys!")

6 toucher.inventory:add(Key{color=world.colors.RED})

7 toucher.inventory:add(Key{color=world.colors.PURPLE})

8 self:die()

9 return true

10end

Changing the rules

MegaZeux has a couple kinds of built-in objects that are difficult to replicate — and thus difficult to customize.

One is projectiles, mentioned earlier. Several variants exist, and a handful of specific behaviors can be toggled with board or world settings, but otherwise that’s all you get. It should be feasible to replicate them all with robots, but I suspect it’d involve a lot of subtleties.

Another is terrain. MegaZeux has a concept of a floor layer (though this is not explicitly exposed in the editor) and some floor tiles have different behavior. Ice is slippery; forest blocks almost everything but can be trampled by the player; lava hurts the player a lot; fire hurts the player and can spread, but burns out after a while. The trick with replicating these is that robots cannot be walked on. An alternative is to use sensors, which can be walked on and which can be controlled by a robot, but anything other than the player will push a sensor rather than stepping onto it. The only other approach I can think of is to keep track of all tiles that have a custom terrain, draw or animate them manually with custom floor tiles, and constantly check whether something’s standing there.

Last are powerups, which are really effects that rings or potions can give you. Some of them are special cases of effects that Robotic can do more generally, such as giving 10 health or changing all of one object into another. Some are completely custom engine stuff, like “Slow Time”, which makes everything on the board (even robots!) run at half speed. The latter are the ones you can’t easily emulate. What if you want to run everything at a quarter speed, for whatever reason? Well, you can’t, short of replacing everything with robots and doing a multiplication every time they wait.

ZDoom has a similar problem: it offers fixed sets of behaviors and powerups (which mostly derive from the commercial games it supports) and that’s it. You can manually script other stuff and go quite far, but some surprisingly simple ideas are very difficult to implement, just because the engine doesn’t offer the right kind of hook.

The tricky part of a generic engine is that a game creator will eventually want to change the rules, and they can only do that if the engine has rules for changing those rules. If the engine devs never thought of it, you’re out of luck.

Someone else please carry on this legacy

MegaZeux still sees development activity, but it’s very sporadic — the last release was in 2012. New features tend to be about making the impossible possible, rather than making the difficult easier. I think it’s safe to call MegaZeux finished, in the sense that a novel is finished.

I would really like to see something pick up its torch. It’s a very tricky problem, especially with the sprawling complexity of games, but surely it’s worth giving non-developers a way to try out the field.

I suppose if ZZT and MegaZeux and ZDoom have taught us anything, it’s that the best way to get started is to just write a game and give it very flexible editing tools. Maybe we should do that more. Maybe I’ll try to do it with Isaac’s Descent HD, and we’ll see how it turns out.

![[articles]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-articles.png)