Hi. Yes. Sorry. I’ve been trying to write this post for ages, but I’ve also been working on a huge writing project, and apparently I have a very limited amount of writing mana at my disposal. I think this is supposed to be a Patreon reward from January. My bad. I hope it’s super great to make up for the wait!

I recently ported some math code from C++ to Rust in an attempt to do a cool thing with Doom. Here is my story.

The problem

I presented it recently as a conundrum (spoilers: I solved it!), but most of those details are unimportant.

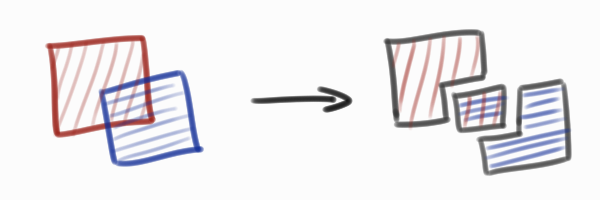

The short version is: I have some shapes. I want to find their intersection.

Really, I want more than that: I want to drop them all on a canvas, intersect everything with everything, and pluck out all the resulting polygons. The input is a set of cookie cutters, and I want to press them all down on the same sheet of dough and figure out what all the resulting contiguous pieces are. And I want to know which cookie cutter(s) each piece came from.

But intersection is a good start.

I’m carefully referring to the input as shapes rather than polygons, because each one could be a completely arbitrary collection of lines. Obviously there’s not much you can do with shapes that aren’t even closed, but at the very least, I need to handle concavity and multiple disconnected polygons that together are considered a single input.

This is a non-trivial problem with a lot of edge cases, and offhand I don’t know how to solve it robustly. I’m not too eager to go figure it out from scratch, so I went hunting for something I could build from.

(Infuriatingly enough, I can just dump all the shapes out in an SVG file and any SVG viewer can immediately solve the problem, but that doesn’t quite help me. Though I have had a few people suggest I just rasterize the whole damn problem, and after all this, I’m starting to think they may have a point.)

Alas, I couldn’t find a Rust library for doing this. I had a hard time finding any library for doing this that wasn’t a massive fully-featured geometry engine. (I could’ve used that, but I wanted to avoid non-Rust dependencies if possible, since distributing software is already enough of a nightmare.)

A Twitter follower directed me towards a paper that described how to do very nearly what I wanted and nothing else: “A simple algorithm for Boolean operations on polygons” by F. Martínez (2013). Being an academic paper, it’s trapped in paywall hell; sorry about that. (And as I understand it, none of the money you’d pay to get the paper would even go to the authors? Is that right? What a horrible and predatory system for discovering and disseminating knowledge.)

The paper isn’t especially long, but it does describe an awful lot of subtle details and is mostly written in terms of its own reference implementation. Rather than write my own implementation based solely on the paper, I decided to try porting the reference implementation from C++ to Rust.

And so I fell down the rabbit hole.

The basic algorithm

Thankfully, the author has published the sample code on his own website, if you want to follow along. (It’s the bottom link; the same author has, confusingly, published two papers on the same topic with similar titles, four years apart.)

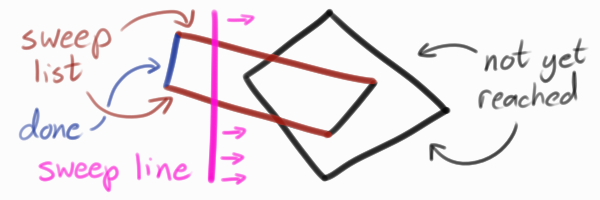

If not, let me describe the algorithm and how the code is generally laid out. The algorithm itself is based on a sweep line, where a vertical line passes across the plane and ✨ does stuff ✨ as it encounters various objects. This implementation has no physical line; instead, it keeps track of which segments from the original polygon would be intersecting the sweep line, which is all we really care about.

The code is all bundled inside a class with only a single public method, run, because… that’s… more object-oriented, I guess. There are several helper methods, and state is stored in some attributes. A rough outline of run is:

-

Run through all the line segments in both input polygons. For each one, generate two

SweepEvents (one for each endpoint) and add them to astd::dequefor storage.Add pointers to the two

SweepEvents to astd::priority_queue, the event queue. This queue uses a custom comparator to order the events from left to right, so the top element is always the leftmost endpoint. -

Loop over the event queue (where an “event” means the sweep line passed over the left or right end of a segment). Encountering a left endpoint means the sweep line is newly touching that segment, so add it to a

std::setcalled the sweep list. An important point is thatstd::setis ordered, and the sweep list uses a comparator that keeps segments in order vertically.Encountering a right endpoint means the sweep line is leaving a segment, so that segment is removed from the sweep list.

-

When a segment is added to the sweep list, it may have up to two neighbors: the segment above it and the segment below it. Call

possibleIntersectionto check whether it intersects either of those neighbors. (This is nearly sufficient to find all intersections, which is neat.) -

If

possibleIntersectiondetects an intersection, it will split each segment into two pieces then and there. The old segment is shortened in-place to become the left part, and a new segment is created for the right part. The new endpoints at the point of intersection are added to the event queue. -

Some bookkeeping is done along the way to track which original polygons each segment is inside, and eventually the segments are reconstructed into new polygons.

Hopefully that’s enough to follow along. It took me an inordinately long time to tease this out. The comments aren’t especially helpful.

1 std::deque<SweepEvent> eventHolder; // It holds the events generated during the computation of the boolean operation

Syntax and basic semantics

The first step was to get something that rustc could at least parse, which meant translating C++ syntax to Rust syntax.

This was surprisingly straightforward! C++ classes become Rust structs. (There was no inheritance here, thankfully.) All the method declarations go away. Method implementations only need to be indented and wrapped in impl.

I did encounter some unnecessarily obtuse uses of the ternary operator:

1(prevprev != sl.begin()) ? --prevprev : prevprev = sl.end();

Rust doesn’t have a ternary — you can use a regular if block as an expression — so I expanded these out.

C++ switch blocks become Rust match blocks, but otherwise function basically the same. Rust’s enums are scoped (hallelujah), so I had to explicitly spell out where enum values came from.

The only really annoying part was changing function signatures; C++ types don’t look much at all like Rust types, save for the use of angle brackets. Rust also doesn’t pass by implicit reference, so I needed to sprinkle a few &s around.

I would’ve had a much harder time here if this code had relied on any remotely esoteric C++ functionality, but thankfully it stuck to pretty vanilla features.

Language conventions

This is a geometry problem, so the sample code unsurprisingly has its own home-grown point type. Rather than port that type to Rust, I opted to use the popular euclid crate. Not only is it code I didn’t have to write, but it already does several things that the C++ code was doing by hand inline, like dot products and cross products. And all I had to do was add one line to Cargo.toml to use it! I have no idea how anyone writes C or C++ without a package manager.

The C++ code used getters, i.e. point.x (). I’m not a huge fan of getters, though I do still appreciate the need for them in lowish-level systems languages where you want to future-proof your API and the language wants to keep a clear distinction between attribute access and method calls. But this is a point, which is nothing more than two of the same numeric type glued together; what possible future logic might you add to an accessor? The euclid authors appear to side with me and leave the coordinates as public fields, so I took great joy in removing all the superfluous parentheses.

Polygons are represented with a Polygon class, which has some number of Contours. A contour is a single contiguous loop. Something you’d usually think of as a polygon would only have one, but a shape with a hole would have two: one for the outside, one for the inside. The weird part of this arrangement was that Polygon implemented nearly the entire STL container interface, then waffled between using it and not using it throughout the rest of the code. Rust lets anything in the same module access non-public fields, so I just skipped all that and used polygon.contours directly. Hell, I think I made contours public.

Finally, the SweepEvent type has a pol field that’s declared as an enum PolygonType (either SUBJECT or CLIPPING, to indicate which of the two inputs it is), but then some other code uses the same field as a numeric index into a polygon’s contours. Boy I sure do love static typing where everything’s a goddamn integer. I wanted to extend the algorithm to work on arbitrarily many input polygons anyway, so I scrapped the enum and this became a usize.

Then I got to all the uses of STL. I have only a passing familiarity with the C++ standard library, and this code actually made modest use of it, which caused some fun days-long misunderstandings.

As mentioned, the SweepEvents are stored in a std::deque, which is never read from. It took me a little thinking to realize that the deque was being used as an arena: it’s the canonical home for the structs so pointers to them can be tossed around freely. (It can’t be a std::vector, because that could reallocate and invalidate all the pointers; std::deque is probably a doubly-linked list, and guarantees no reallocation.)

Rust’s standard library does have a doubly-linked list type, but I knew I’d run into ownership hell here later anyway, so I think I replaced it with a Rust Vec to start with. It won’t compile either way, so whatever. We’ll get back to this in a moment.

The list of segments currently intersecting the sweep line is stored in a std::set. That type is explicitly ordered, which I’m very glad I knew already. Rust has two set types, HashSet and BTreeSet; unsurprisingly, the former is unordered and the latter is ordered. Dropping in BTreeSet and fixing some method names got me 90% of the way there.

Which brought me to the other 90%. See, the C++ code also relies on finding nodes adjacent to the node that was just inserted, via STL iterators.

1next = prev = se->posSL = it = sl.insert(se).first;

2(prev != sl.begin()) ? --prev : prev = sl.end();

3++next;

I freely admit I’m bad at C++, but this seems like something that could’ve used… I don’t know, 1 comment. Or variable names more than two letters long. What it actually does is:

-

Add the current sweep event (

se) to the sweep list (sl), which returns a pair whose first element is an iterator pointing at the just-inserted event. -

Copies that iterator to several other variables, including

prevandnext. -

If the event was inserted at the beginning of the sweep list, set

prevto the sweep list’senditerator, which in C++ is a legal-but-invalid iterator meaning “the space after the end” or something. This is checked for in later code, to see if there is a previous event to look at. Otherwise, decrementprev, so it’s now pointing at the event immediately before the inserted one. -

Increment

nextnormally. If the inserted event is last, then this will bumpnextto theenditerator anyway.

In other words, I need to get the previous and next elements from a BTreeSet. Rust does have bidirectional iterators, which BTreeSet supports… but BTreeSet::insert only returns a bool telling me whether or not anything was inserted, not the position. I came up with this:

1let mut maybe_below = active_segments.range(..segment).last().map(|v| *v);

2let mut maybe_above = active_segments.range(segment..).next().map(|v| *v);

3active_segments.insert(segment);

The range method returns an iterator over a subset of the tree. The .. syntax makes a range (where the right endpoint is exclusive), so ..segment finds the part of the tree before the new segment, and segment.. finds the part of the tree after it. (The latter would start with the segment itself, except I haven’t inserted it yet, so it’s not actually there.)

Then the standard next() and last() methods on bidirectional iterators find me the element I actually want. But the iterator might be empty, so they both return an Option. Also, iterators tend to return references to their contents, but in this case the contents are already references, and I don’t want a double reference, so the map call dereferences one layer — but only if the Option contains a value. Phew!

This is slightly less efficient than the C++ code, since it has to look up where segment goes three times rather than just one. I might be able to get it down to two with some more clever finagling of the iterator, but microsopic performance considerations were a low priority here.

Finally, the event queue uses a std::priority_queue to keep events in a desired order and efficiently pop the next one off the top.

Except priority queues act like heaps, where the greatest (i.e., last) item is made accessible.

Sorting out sorting

C++ comparison functions return true to indicate that the first argument is less than the second argument. Sweep events occur from left to right. You generally implement sorts so that the first thing comes, erm, first.

But sweep events go in a priority queue, and priority queues surface the last item, not the first. This C++ code handled this minor wrinkle by implementing its comparison backwards.

1struct SweepEventComp : public std::binary_function<SweepEvent, SweepEvent, bool> { // for sorting sweep events

2// Compare two sweep events

3// Return true means that e1 is placed at the event queue after e2, i.e,, e1 is processed by the algorithm after e2

4bool operator() (const SweepEvent* e1, const SweepEvent* e2)

5{

6 if (e1->point.x () > e2->point.x ()) // Different x-coordinate

7 return true;

8 if (e2->point.x () > e1->point.x ()) // Different x-coordinate

9 return false;

10 if (e1->point.y () != e2->point.y ()) // Different points, but same x-coordinate. The event with lower y-coordinate is processed first

11 return e1->point.y () > e2->point.y ();

12 if (e1->left != e2->left) // Same point, but one is a left endpoint and the other a right endpoint. The right endpoint is processed first

13 return e1->left;

14 // Same point, both events are left endpoints or both are right endpoints.

15 if (signedArea (e1->point, e1->otherEvent->point, e2->otherEvent->point) != 0) // not collinear

16 return e1->above (e2->otherEvent->point); // the event associate to the bottom segment is processed first

17 return e1->pol > e2->pol;

18}

19};

Maybe it’s just me, but I had a hell of a time just figuring out what problem this was even trying to solve. I still have to reread it several times whenever I look at it, to make sure I’m getting the right things backwards.

Making this even more ridiculous is that there’s a second implementation of this same sort, with the same name, in another file — and that one’s implemented forwards. And doesn’t use a tiebreaker. I don’t entirely understand how this even compiles, but it does!

I painstakingly translated this forwards to Rust. Unlike the STL, Rust doesn’t take custom comparators for its containers, so I had to implement ordering on the types themselves (which makes sense, anyway). I wrapped everything in the priority queue in a Reverse, which does what it sounds like.

I’m fairly pleased with Rust’s ordering model. Most of the work is done in Ord, a trait with a cmp() method returning an Ordering (one of Less, Equal, and Greater). No magic numbers, no need to implement all six ordering methods! It’s incredible. Ordering even has some handy methods on it, so the usual case of “order by this, then by this” can be written as:

1return self.point().x.cmp(&other.point().x)

2 .then(self.point().y.cmp(&other.point().y));

Well. Just kidding! It’s not quite that easy. You see, the points here are composed of floats, and floats have the fun property that not all of them are comparable. Specifically, NaN is not less than, greater than, or equal to anything else, including itself. So IEEE 754 float ordering cannot be expressed with Ord. Unless you want to just make up an answer for NaN, but Rust doesn’t tend to do that.

Rust’s float types thus implement the weaker PartialOrd, whose method returns an Option<Ordering> instead. That makes the above example slightly uglier:

1return self.point().x.partial_cmp(&other.point().x).unwrap()

2 .then(self.point().y.partial_cmp(&other.point().y).unwrap())

Also, since I use unwrap() here, this code will panic and take the whole program down if the points are infinite or NaN. Don’t do that.

This caused some minor inconveniences in other places; for example, the general-purpose cmp::min() doesn’t work on floats, because it requires an Ord-erable type. Thankfully there’s a f64::min(), which handles a NaN by returning the other argument.

(Cool story: for the longest time I had this code using f32s. I’m used to translating int to “32 bits”, and apparently that instinct kicked in for floats as well, even floats spelled double.)

The only other sorting adventure was this:

1// Due to overlapping edges the resultEvents array can be not wholly sorted

2bool sorted = false;

3while (!sorted) {

4 sorted = true;

5 for (unsigned int i = 0; i < resultEvents.size (); ++i) {

6 if (i + 1 < resultEvents.size () && sec (resultEvents[i], resultEvents[i+1])) {

7 std::swap (resultEvents[i], resultEvents[i+1]);

8 sorted = false;

9 }

10 }

11}

(I originally misread this comment as saying “the array cannot be wholly sorted” and had no idea why that would be the case, or why the author would then immediately attempt to bubble sort it.)

I’m still not sure why this uses an ad-hoc sort instead of std::sort. But I’m used to taking for granted that general-purpose sorting implementations are tuned to work well for almost-sorted data, like Python’s. Maybe C++ is untrustworthy here, for some reason. I replaced it with a call to .sort() and all seemed fine.

Phew! We’re getting there. Finally, my code appears to type-check.

But now I see storm clouds gathering on the horizon.

Ownership hell

I have a problem. I somehow run into this problem every single time I use Rust. The solutions are never especially satisfying, and all the hacks I might use if forced to write C++ turn out to be unsound, which is even more annoying because rustc is just sitting there with this smug “I told you so expression” and—

The problem is ownership, which Rust is fundamentally built on. Any given value must have exactly one owner, and Rust must be able to statically convince itself that:

- No reference to a value outlives that value.

- If a mutable reference to a value exists, no other references to that value exist at the same time.

This is the core of Rust. It guarantees at compile time that you cannot lose pointers to allocated memory, you cannot double-free, you cannot have dangling pointers.

It also completely thwarts a lot of approaches you might be inclined to take if you come from managed languages (where who cares, the GC will take care of it) or C++ (where you just throw pointers everywhere and hope for the best apparently).

For example, pointer loops are impossible. Rust’s understanding of ownership and lifetimes is hierarchical, and it simply cannot express loops. (Rust’s own doubly-linked list type uses raw pointers and unsafe code under the hood, where “unsafe” is an escape hatch for the usual ownership rules. Since I only recently realized that pointers to the inside of a mutable Vec are a bad idea, I figure I should probably not be writing unsafe code myself.)

This throws a few wrenches in the works.

Problem the first: pointer loops

I immediately ran into trouble with the SweepEvent struct itself. A SweepEvent pulls double duty: it represents one endpoint of a segment, but each left endpoint also handles bookkeeping for the segment itself — which means that most of the fields on a right endpoint are unused. Also, and more importantly, each SweepEvent has a pointer to the corresponding SweepEvent at the other end of the same segment. So a pair of SweepEvents point to each other.

Rust frowns upon this. In retrospect, I think I could’ve kept it working, but I also think I’m wrong about that.

My first step was to wrench SweepEvent apart. I moved all of the segment-stuff (which is virtually all of it) into a single SweepSegment type, and then populated the event queue with a SweepEndpoint tuple struct, similar to:

1enum SegmentEnd {

2 Left,

3 Right,

4}

5

6struct SweepEndpoint<'a>(&'a SweepSegment, SegmentEnd);

This makes SweepEndpoint essentially a tuple with a name. The 'a is a lifetime and says, more or less, that a SweepEndpoint cannot outlive the SweepSegment it references. Makes sense.

Problem solved! I no longer have mutually referential pointers. But I do still have pointers (well, references), and they have to point to something.

Problem the second: where's all the data

Which brings me to the problem I always run into with Rust. I have a bucket of things, and I need to refer to some of them multiple times.

I tried half a dozen different approaches here and don’t clearly remember all of them, but I think my core problem went as follows. I translated the C++ class to a Rust struct with some methods hanging off of it. A simplified version might look like this.

1struct Algorithm {

2 arena: LinkedList<SweepSegment>,

3 event_queue: BinaryHeap<SweepEndpoint>,

4}

Ah, hang on — SweepEndpoint needs to be annotated with a lifetime, so Rust can enforce that those endpoints don’t live longer than the segments they refer to. No problem?

1struct Algorithm<'a> {

2 arena: LinkedList<SweepSegment>,

3 event_queue: BinaryHeap<SweepEndpoint<'a>>,

4}

Okay! Now for some methods.

1fn run(&mut self) {

2 self.arena.push_back(SweepSegment{ data: 5 });

3 self.event_queue.push(SweepEndpoint(self.arena.back().unwrap(), SegmentEnd::Left));

4 self.event_queue.push(SweepEndpoint(self.arena.back().unwrap(), SegmentEnd::Right));

5 for event in &self.event_queue {

6 println!("{:?}", event)

7 }

8}

Aaand… this doesn’t work. Rust “cannot infer an appropriate lifetime for autoref due to conflicting requirements”. The trouble is that self.arena.back() takes a reference to self.arena, and then I put that reference in the event queue. But I promised that everything in the event queue has lifetime 'a, and I don’t actually know how long self lives here; I only know that it can’t outlive 'a, because that would invalidate the references it holds.

A little random guessing let me to change &mut self to &'a mut self — which is fine because the entire impl block this lives in is already parameterized by 'a — and that makes this compile! Hooray! I think that’s because I’m saying self itself has exactly the same lifetime as the references it holds onto, which is true, since it’s referring to itself.

Let’s get a little more ambitious and try having two segments.

1fn run(&'a mut self) {

2 self.arena.push_back(SweepSegment{ data: 5 });

3 self.event_queue.push(SweepEndpoint(self.arena.back().unwrap(), SegmentEnd::Left));

4 self.event_queue.push(SweepEndpoint(self.arena.back().unwrap(), SegmentEnd::Right));

5 self.arena.push_back(SweepSegment{ data: 17 });

6 self.event_queue.push(SweepEndpoint(self.arena.back().unwrap(), SegmentEnd::Left));

7 self.event_queue.push(SweepEndpoint(self.arena.back().unwrap(), SegmentEnd::Right));

8 for event in &self.event_queue {

9 println!("{:?}", event)

10 }

11}

Whoops! Rust complains that I’m trying to mutate self.arena while other stuff is referring to it. And, yes, that’s true — I have references to it in the event queue, and Rust is preventing me from potentially deleting everything from the queue when references to it still exist. I’m not actually deleting anything here, of course (though I could be if this were a Vec!), but Rust’s type system can’t encode that (and I dread the thought of a type system that can).

I struggled with this for a while, and rapidly encountered another complete showstopper:

1fn run(&'a mut self) {

2 self.mutate_something();

3 self.mutate_something();

4}

5

6fn mutate_something(&'a mut self) {}

Rust objects that I’m trying to borrow self mutably, twice — once for the first call, once for the second.

But why? A borrow is supposed to end automatically once it’s no longer used, right? Maybe if I throw some braces around it for scope… nope, that doesn’t help either.

It’s true that borrows usually end automatically, but here I have explicitly told Rust that mutate_something() should borrow with the lifetime 'a, which is the same as the lifetime in run(). So the first call explicitly borrows self for at least the rest of the method. Removing the lifetime from mutate_something() does fix this error, but if that method tries to add new segments, I’m back to the original problem.

Oh no. The mutation in the C++ code is several calls deep. Porting it directly seems nearly impossible.

The typical solution here — at least, the first thing people suggest to me on Twitter — is to wrap basically everything everywhere in Rc<RefCell<T>>, which gives you something that’s reference-counted (avoiding questions of ownership) and defers borrow checks until runtime (avoiding questions of mutable borrows). But that seems pretty heavy-handed here — not only does RefCell add .borrow() noise anywhere you actually want to interact with the underlying value, but do I really need to refcount these tiny structs that only hold a handful of floats each?

I set out to find a middle ground.

Solution, kind of

I really, really didn’t want to perform serious surgery on this code just to get it to build. I still didn’t know if it worked at all, and now I had to rearrange it without being able to check if I was breaking it further. (This isn’t Rust’s fault; it’s a natural problem with porting between fairly different paradigms.)

So I kind of hacked it into working with minimal changes, producing a grotesque abomination which I’m ashamed to link to. Here’s how!

First, I got rid of the class. It turns out this makes lifetime juggling much easier right off the bat. I’m pretty sure Rust considers everything in a struct to be destroyed simultaneously (though in practice it guarantees it’ll destroy fields in order), which doesn’t leave much wiggle room. Locals within a function, on the other hand, can each have their own distinct lifetimes, which solves the problem of expressing that the borrows won’t outlive the arena.

Speaking of the arena, I solved the mutability problem there by switching to… an arena! The typed-arena crate (a port of a type used within Rust itself, I think) is an allocator — you give it a value, and it gives you back a reference, and the reference is guaranteed to be valid for as long as the arena exists. The method that does this is sneaky and takes &self rather than &mut self, so Rust doesn’t know you’re mutating the arena and won’t complain. (One drawback is that the arena will never free anything you give to it, but that’s not a big problem here.)

My next problem was with mutation. The main loop repeatedly calls possibleIntersection with pairs of segments, which can split either or both segment. Rust definitely doesn’t like that — I’d have to pass in two &muts, both of which are mutable references into the same arena, and I’d have a bunch of immutable references into that arena in the sweep list and elsewhere. This isn’t going to fly.

This is kind of a shame, and is one place where Rust seems a little overzealous. Something like this seems like it ought to be perfectly valid:

1let mut v = vec![1u32, 2u32];

2let a = &mut v[0];

3let b = &mut v[1];

4// do stuff with a, b

The trouble is, Rust only knows the type signature, which here is something like index_mut(&'a mut self, index: usize) -> &'a T. Nothing about that says that you’re borrowing distinct elements rather than some core part of the type — and, in fact, the above code is only safe because you’re borrowing distinct elements. In the general case, Rust can’t possibly know that. It seems obvious enough from the different indexes, but nothing about the type system even says that different indexes have to return different values. And what if one were borrowed as &mut v[1] and the other were borrowed with v.iter_mut().next().unwrap()?

Anyway, this is exactly where people start to turn to RefCell — if you’re very sure you know better than Rust, then a RefCell will skirt the borrow checker while still enforcing at runtime that you don’t have more than one mutable borrow at a time.

But half the lines in this algorithm examine the endpoints of a segment! I don’t want to wrap the whole thing in a RefCell, or I’ll have to say this everywhere:

1if segment1.borrow().point.x < segment2.borrow().point.x { ... }

Gross.

But wait — this code only mutates the points themselves in one place. When a segment is split, the original segment becomes the left half, and a new segment is created to be the right half. There’s no compelling need for this; it saves an allocation for the left half, but it’s not critical to the algorithm.

Thus, I settled on a compromise. My segment type now looks like this:

1struct SegmentPacket {

2 // a bunch of flags and whatnot used in the algorithm

3}

4struct SweepSegment {

5 left_point: MapPoint,

6 right_point: MapPoint,

7 faces_outwards: bool,

8 index: usize,

9 order: usize,

10 packet: RefCell<SegmentPacket>,

11}

I do still need to call .borrow() or .borrow_mut() to get at the stuff in the “packet”, but that’s far less common, so there’s less noise overall. And I don’t need to wrap it in Rc because it’s part of a type that’s allocated in the arena and passed around only via references.

This still leaves me with the problem of how to actually perform the splits.

I’m not especially happy with what I came up with, I don’t know if I can defend it, and I suspect I could do much better. I changed possibleIntersection so that rather than performing splits, it returns the points at which each segment needs splitting, in the form (usize, Option<MapPoint>, Option<MapPoint>). (The usize is used as a flag for calling code and oughta be an enum, but, isn’t yet.)

Now the top-level function is responsible for all arena management, and all is well.

Except, er. possibleIntersection is called multiple times, and I don’t want to copy-paste a dozen lines of split code after each call. I tried putting just that code in its own function, which had the world’s most godawful signature, and that didn’t work because… uh… hm. I can’t remember why, exactly! Should’ve written that down.

I tried a local closure next, but closures capture their environment by reference, so now I had references to a bunch of locals for as long as the closure existed, which meant I couldn’t mutate those locals. Argh. (This seems a little silly to me, since the closure’s references cannot possibly be used for anything if the closure isn’t being called, but maybe I’m missing something. Or maybe this is just a limitation of lifetimes.)

Increasingly desperate, I tried using a macro. But… macros are hygienic, which means that any new name you use inside a macro is different from any name outside that macro. The macro thus could not see any of my locals. Usually that’s good, but here I explicitly wanted the macro to mess with my locals.

I was just about to give up and go live as a hermit in a cabin in the woods, when I discovered something quite incredible. You can define local macros! If you define a macro inside a function, then it can see any locals defined earlier in that function. Perfect!

1macro_rules! _split_segment (

2 ($seg:expr, $pt:expr) => (

3 {

4 let pt = $pt;

5 let seg = $seg;

6 // ... waaay too much code ...

7 }

8 );

9);

10

11loop {

12 // ...

13 // This is possibleIntersection, renamed because Rust rightfully complains about camelCase

14 let cross = handle_intersections(Some(segment), maybe_above);

15 if let Some(pt) = cross.1 {

16 segment = _split_segment!(segment, pt);

17 }

18 if let Some(pt) = cross.2 {

19 maybe_above = Some(_split_segment!(maybe_above.unwrap(), pt));

20 }

21 // ...

22}

(This doesn’t actually quite match the original algorithm, which has one case where a segment can be split twice. I realized that I could just do the left-most split, and a later iteration would perform the other split. I sure hope that’s right, anyway.)

It’s a bit ugly, and I ran into a whole lot of implicit behavior from the C++ code that I had to fix — for example, the segment is sometimes mutated just before it’s split, purely as a shortcut for mutating the left part of the split. But it finally compiles! And runs! And kinda worked, a bit!

Aftermath

I still had a lot of work to do.

For one, this code was designed for intersecting two shapes, not mass-intersecting a big pile of shapes. The basic algorithm doesn’t care about how many polygons you start with — all it sees is segments — but the code for constructing the return value needed some heavy modification.

The biggest change by far? The original code traced each segment once, expecting the result to be only a single shape. I had to change that to trace each side of each segment once, since the vast bulk of the output consists of shapes which share a side. This violated a few assumptions, which I had to hack around.

I also ran into a couple very bad edge cases, spent ages debugging them, then found out that the original algorithm had a subtle workaround that I’d commented out because it was awkward to port but didn’t seem to do anything. Whoops!

The worst was a precision error, where a vertical line could be split on a point not quite actually on the line, which wreaked all kinds of havoc. I worked around that with some tasteful rounding, which is highly dubious but makes the output more appealing to my squishy human brain. (I might switch to the original workaround, but I really dislike that even simple cases can spit out points at 1500.0000000000003. The whole thing is parameterized over the coordinate type, so maybe I could throw a rational type in there and cross my fingers?)

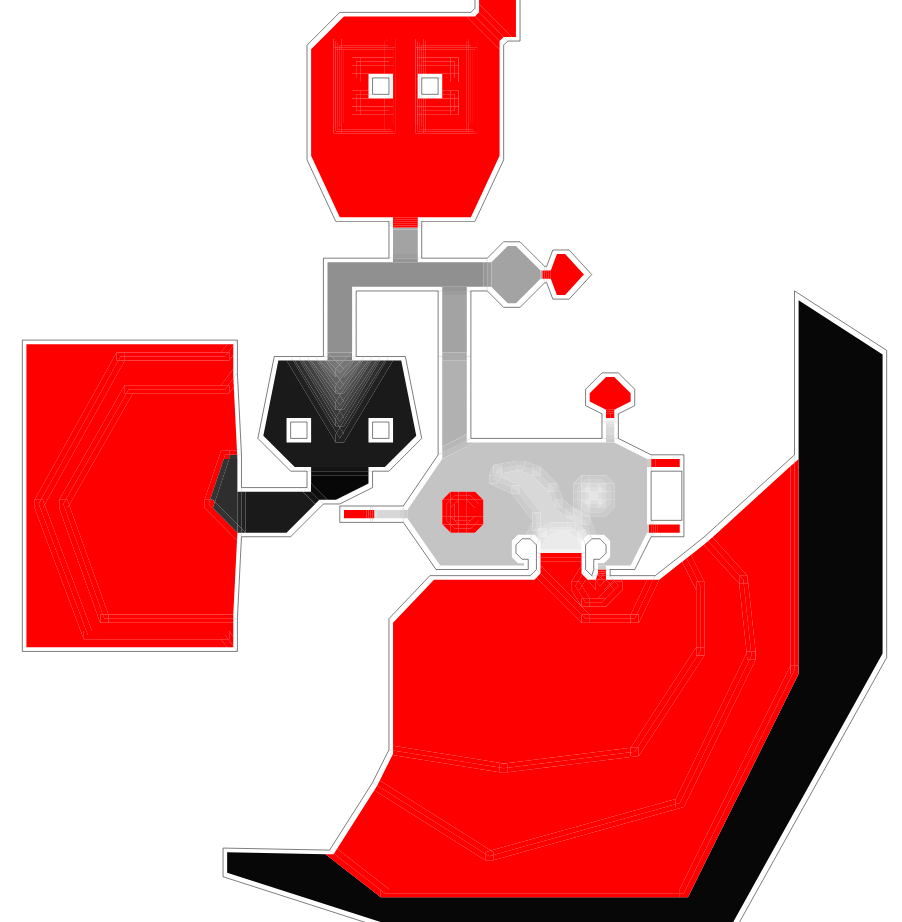

All that done, I finally, finally, after a couple months of intermittent progress, got what I wanted!

This is Doom 2’s MAP01. The black area to the left of center is where the player starts. Gray areas indicate where the player can walk from there, with lighter shades indicating more distant areas, where “distance” is measured by the minimum number of line crossings. Red areas can’t be reached at all.

(Note: large playable chunks of the map, including the exit room, are red. That’s because those areas are behind doors, and this code doesn’t understand doors yet.)

(Also note: The big crescent in the lower-right is also black because I was lazy and looked for the player’s starting sector by checking the bbox, and that sector’s bbox happens to match.)

The code that generated this had to go out of its way to delete all the unreachable zones around solid walls. I think I could modify the algorithm to do that on the fly pretty easily, which would probably speed it up a bit too. Downside is that the algorithm would then be pretty specifically tied to this problem, and not usable for any other kind of polygon intersection, which I would think could come up elsewhere? The modifications would be pretty minor, though, so maybe I could confine them to a closure or something.

Some final observations

It runs surprisingly slowly. Like, multiple seconds. Unless I add --release, which speeds it up by a factor of… some number with multiple digits. Wahoo. Debug mode has a high price, especially with a lot of calls in play.

The current state of this code is on GitHub. Please don’t look at it. I’m very sorry.

Honestly, most of my anguish came not from Rust, but from the original code relying on lots of fairly subtle behavior without bothering to explain what it was doing or even hint that anything unusual was going on. God, I hate C++.

I don’t know if the Rust community can learn from this. I don’t know if I even learned from this. Let’s all just quietly forget about it.

Now I just need to figure this one out…

![[process]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-process.png)