Mel and I made a game!

We’d wanted to a small game together for a while. Last month’s post about embedding Lua reminded me of the existence of the PICO-8, a “fantasy console” with 8-bit-ish limitations and built-in editing tools. Both of us have a bad habit of letting ambitions spiral way out of control, so “built-in limitations” sounded pretty good to me. I bought the console ($15, or free with the $20 Voxatron alpha) on a whim and started tinkering with it.

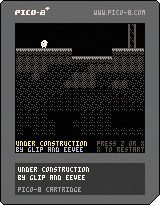

The result: Under Construction!

You can play in your very own web browser, assuming you have a keyboard. Also, that image is the actual cartridge, which you can save and play directly if you happen to have PICO-8. It’s also in the PICO-8 BBS.

(A couple people using Chrome on OS X have reported a very early crash, which seems to be a bug outside of my control. Safari works, and merely restarting Chrome has fixed it for at least one person.)

I don’t have too much to say about the game itself; hopefully, it speaks for itself. If not, there’s a little more on its Floraverse post.

I do have some things to say about making it. Also I am really, really tired, so apologies if this is even more meandering than usual.

The PICO-8

You can get a quick idea of what the console is all about from the homepage. I say “console”, but of course, there’s no physical hardware — the PICO-8 is a game engine with some severe artificial restrictions. It’s kind of like an emulator for a console that never existed.

Feel free to pore over the manual, but the most obvious limitations are:

-

Screen resolution of 128×128, usually displayed scaled up, since that’s microscopic on modern monitors.

-

16-color fixed palette. The colors you see in the screenshots are the only colors you can use, period.

-

A spritesheet with enough room for 256 8×8 sprites. (You can make and use larger sprites, or use the space for something else entirely if you want, but the built-in tools assume you generally want that sprite size.)

-

A 128×64 map, as measured in tiles. The screen is 16×16 tiles, so that’s enough space for 32 screenfuls.

-

Alas! Half of the sprite space and half of the map space are shared, so you can’t actually have both 256 sprites and 32 map screens. You can have 256 sprites and 16 map screens, or 128 sprites and 32 map screens (which is what we did), or split the shared space some other way.

-

64 chiptuney sound effects, complete with a tiny tracker for creating them.

-

64 music tracks, built out of loops of up to four sound effects. There are only four sound channels total, so having four-channel background music means you can’t play any sound effects on top of it.

The programming language is a modified Lua, which comes with its own restrictions, but I’ll get to those later.

The restrictions are “carefully chosen to be fun to work with, [and] encourage small but expressive designs”. For the most part, they succeeded.

Our process

I bought PICO-8 at the beginning of the month. I spent a few hours a day over the next several days messing around, gradually producing a tiny non-game I called “eeveequest” and tweeting out successive iterations. I added the basics as they came to mind, without any real goal: movement, collision, jumping, music, sound effects, scrolling, camera movement.

The PICO-8 did let me create something with all the usual parts of a game in a matter of hours, and that’s pretty cool. I’ve never made music before, save for an hour or two trying to get audio working with LMMS, but I managed even a simple tune and some chimes here.

Meanwhile, Mel was independently trying it out, drawing sprites and populating a map. I copied my movement code over to their cartridge so we could walk around in this little world.

Then, uh, they gave me an avalanche of text describing what they wanted, and I vanished from the mortal realm for ten days while I set about making it happen.

Look, I didn’t say this was a good process. Our next endeavor should be a little more balanced, since we won’t be eight hours apart, and a good chunk of engine code is already written.

One particularly nice thing: PICO-8 cartridges are very simple text files with the code at the top. I eventually migrated to writing code in vim rather than the (extremely simple) built-in code editor, and if Mel had been working on the map at the same time, I could just copy-paste everything except the code into my own cart. It would play decently well with source control, but for a two-person project where I’m the only one editing the code, I couldn’t really justify inflicting git on a non-programmer. We did have one minor incident where a few map changes were lost, but for the most part, it worked surprisingly well for collaborating between a programmer and an artist.

There was a lot more back-and-forth towards the end, once the bulk of the code was written (and Mel was no longer busy selling at three conventions), when the remaining work was subtler design issues. That was probably the most fun I had.

Programming the PICO-8

I picked on Lua a bit in that post last month. Having now worked with it for two solid weeks, I regret what I said. Because now I really want to say it all again, more forcefully. Silently ignoring errors (including division by zero!) and having no easy way to print values for debugging are my top two least favorite programming language “features”.

Plenty of Lua is just plain weird, but forgiveable. Those two things make it pretty aggravating. It’s not even for any good reason — Lua clearly has an error-reporting mechanism, so it’s entirely capable of having division by zero be an error. And half the point of a dynamic runtime is that you can easily examine values at runtime, yet Lua makes doing that as difficult as possible. Argh.

PICO-8's Lua

The PICO-8 uses a slightly modified Lua 5.2. The documentation isn’t precise about what parts of Lua are still available, so I had some minor misadventures, like thinking varargs weren’t supported because the arg global was missing. (Turns out varargs work fine, but Lua 5.2 changed the syntax and got rid of the clumsy global.)

If it weren’t yet obvious, I’m no Lua expert. The most obvious differences to me are:

-

Numbers are signed 16.16 fixed-point, rather than Lua’s double-precision floats. (This has the curious side effect that dividing by zero produces 32768.) I have a soft spot for fixed-point! It’s nice sometimes to have a Planck length that doesn’t depend on where you are in the game world.

-

Most of the standard library is missing. There’s no

collectgarbage,error,ipairs,pcall,tostring,unpack, or other more obscure stuff. Thebit32,debug,math,os,string, andtablelibraries are gone. The_Gsuperglobal is gone. -

Several built-ins have been changed or replaced with alternatives:

alliterates over a sequence-like table;pairsiterates over all keys and values in a table;printnow prints to a particular screen coordinate. A handful of substitute math and string functions are built in. There are functions for bit operations, which I guess were in thebit32library. -

There are some mutating assignment operators:

+=,-=,*=,/=,%=. Lua doesn’t have these.

The PICO-8 does still have metatables and coroutines. Metatables were a blessing. Coroutines are nice, but I never came up with a good excuse to use them.

Writing the actual game stuff

Each of the PICO-8’s sprites has a byte’s worth of flags — eight color-coded toggles that can be turned on or off. They don’t mean anything to the console, and you’re free to use them however you want in your game.

I decided early on, even for EeveeQuest™, to use one of the flags to indicate a block was solid. It’s the most obvious approach, and it turned out to have the happy side effect that Mel could change the physics of the game world without touching the code at all. I ended up using five more flags to indicate which acts a tile should appear in.

I love rigging game engines so that people can modify as much stuff as possible without touching code. I already prefer writing code in a more declarative style, and this is even better: the declarations are out of code entirely and in a graphical tool instead.

Game code is generally awful, so I did my best to keep things tidy. First, some brief background.

A game has two major concerns: it has to simulate the world, and it has to draw that world to the screen. The easiest and most obvious approach, then, is to alternate those steps: do a single update pass (where everyone takes one step, say), then draw, then do another update, and so on. One round of updating and drawing is a frame, and the length of time it takes is a tic. If you want your game to run at 60 fps, then a tic is 1/60 seconds, and you have to be sure you can both update once and draw once in that amount of time.

You get into trouble when drawing to the screen starts to take long. Say it takes two tics. Now not only is the display laggy, but the actual game world is running at half speed, because you only run an update pass every two tics instead of every one.

The PICO-8 is not the kind of platform you might expect to have this problem, but nonetheless it offers a very simple solution. It asks your code to update, then it asks your code to draw, separately. If the console detects that the game is running too slowly to hit its usual 30 fps, it’ll automatically slow down its framerate to 15fps, but it’ll ask you to update twice between draws. (Put differently, it skips every other draw.)

This turned out to be handy in act 4, where the fog effect is sometimes a little too intensive. The framerate drops, but the world still moves along at the right speed, so it just looks like the animation isn’t quite as smooth.

I copied this approach all the way down. I have a simple object called a “scene”, which is what you might also call a “screen”: the title screen, playable area, text between acts, and ending credits are all different scenes. The playable scene has a handful of layers, each of which updates and then draws like a stack.

The map is kind of interesting. The PICO-8 has a function for drawing an entire block of the map to the screen, which works pretty well for static stuff like background tiles and solid walls. There’s no built-in support for animation, though, and certainly nothing for handling player movement or tiles that only sometimes exist.

So I made an “actor” type, which can be anything that wants to participate in the usual update/draw cycle. There are three major kinds of actor:

-

Decor shouldn’t move and doesn’t draw itself; instead, it edits its own position on the map. This is used for all the animated sprites, as well as a few static objects like radios.

-

Mobs aren’t on the map at all and can move around freely, possibly colliding with parts of the map and each other. Only the player and the rocks are mobs; each additional one makes collision detection significantly more expensive. (I never got around to adding a blockmap.)

-

Transient actors don’t actually update or draw, and in fact they don’t permanently exist at all. They’re only created temporarily, when the player or another mob bumps into a map tile. When you walk into a wall, for example, the game creates a temporary wall actor at that position that checks its sprite’s flags to see if it blocks you. This is how the spikes work, too; they don’t need to update every tic, because they don’t actually do anything on their own, but they can still have custom behavior when you bump into them. They also have a custom collision box.

You can declare that a specific sprite on the map will always be turned into a particular kind of actor, and give it its own behavior. Virtually everything works this way, even the player, which means you can move the mole sprite anywhere on the map and it’ll automatically become the player’s start point.

You can also define an animation, and it’ll automatically be turned into a type of decor that doesn’t do anything except edit the map every few frames to animate itself.

By far, the worst thing to deal with was collision. I must’ve rewritten it four or five times.

I’ve written collision code before, but apparently I’d never done it from complete scratch for a world with free movement and polished it to a mirror sheen.

Maybe I’m missing something here, but the usual simple approach to collision is terrible. It tends to go like this.

- Move the player some amount in the direction they’re moving.

- See if they’re now overlapping anything.

- If they are, move them back to where they started.

That’s some hot garbage. What if you’re falling, and you’re a pixel above the ground, but you’re moving at two pixels per tic? The game will continually try to move you two pixels, see you’re stuck in the ground, and then put you back where you started. You’ll hover a pixel above the ground forever.

I tried doing some research, by which I mean I googled for three minutes and got sick of finding “tutorials” that didn’t go any further than this useless algorithm, so I just beat on it until I got what I wanted. My approach:

- Get the player’s bounding box. Extend that box in the direction they’re moving, so it covers both their old and new position.

- Get a list of all the actors that overlap that box, including transient actors for every tile. (This is the main place they’re used, so I can handle them the same way as any other actor.)

- Sort all those actors in the order the player will hit them, starting with the closest.

- Look at the first actor. Move the player towards it until they touch it, then stop. If the actor has any collision behavior, activate it now.

- If the actor is solid, you’re done, at least in this direction; drop the actor’s velocity to zero. Otherwise, repeat with the next actor.

- If there’s any movement left at the end, tack that on too, since nothing else can be in the way.

I had some fun bugs along the way, like the one where the collision detection was almost perfect, unless you hit a solid block exactly on its corner, in which case you would pass right through it. Or the multiple times you couldn’t walk along the ground because you were colliding with the corner of the next tile of ground.

This seems to be pretty rock solid now, though it’s a bit slow when there are more than half a dozen or so mobs wandering around. It works well enough for this game.

The runner-up for awkward things to deal with: time. Even a simple animation is mildly annoying. It’s not that the math is difficult; it’s more that you can’t look at the math and immediately understand what it’s doing.

I wished numerous times that I had a more straightforward way to say “fade this in, wait 10 tics, then fade it back out”, but I never had the time to sit down and come up with something nice. I considered using coroutines for this, since they’re naturally sleep-able, but I don’t think they’d work so well for anything beyond the most trivial operations. cocos2d has a concept of “actions”, where you can animate a change over time and even schedule several changes to happen in sequence; maybe I’ll give something like that a try next time.

The PICO-8's limits

Working within limitations has a unique way of inspiring creative solutions. It can even help you get started in a medium you’ve never tried before. I know. It’s the whole point of the console. I only got around to making some music because I was handed a very limited tracker.

Sixteen colors? Well, that’s okay; now I don’t have to worry about picking my own colors, which is something I’m not terribly good at.

Small screen and sprite size? That puts a cap on how good the art can possibly be expected to look anyway, so I can make simple sprites fairly easily and have a decent-looking game.

Limited map space? Well… now we’re getting into fuzzier territory. A limit on map space is less of a creative constraint and more of a hard cap on how much game you can fit in your game. At least you can make up for it in a few ways with some creative programming.

Hmm. About that.

There are three limits on the amount of code you can have:

- No more than 8192 tokens. A token is a single identifier, string, number, or operator. A pair of brackets counts as one token. Commas, periods, colons, and the

localandendkeywords are free. - No more than 65536 bytes. That’s a pretty high limit, and I think it really only exists to prevent you from cramming ludicrous amounts of data into a cartridge via strings.

- No more than 15360 bytes, after compression. More on that in a moment.

I thought 8192 sounded like plenty. Then I went and wrote a game. Our final tally, for my 2779 lines of Lua:

- 8183/8192 tokens

- 56668/65536 bytes

- 22574/15360 compressed bytes

That’s not a typo; I was well over the compressed limit. I only even found out about the compressed limit a few days ago — the documentation never actually mentions it, and the built-in editor only tracks code size and token count! It came as a horrible surprise. For the released version of the game, I had to delete every single comment, remove every trace of debugging code, and rename several local variables. I was resorting to deleting extra blank lines before I finally got it to fit.

Trying to squeeze code into a compressed limit is maddening. Most of the obvious ways to significantly shorten code involve removing duplication, but duplication is exactly what compression algorithms are good at dealing with! Several times I tried an approach that made the code shorter in both absolute size and token count, only to find that the compressed size had grown slightly larger.

As for tokens, wow. I’ve never even had to think in tokens before. Here are some token costs from the finished game.

- 65 — updating the camera to follow the player

- 95 — sort function

- 148 — simple vector type

- 198 — function to print text on the screen aligned to a point

- 201 — debugging function that prints values to stdout

- 256 — perlin noise implementation

- 261 — screen fade

- 280 — fog effect from act 4

- 370 — title screen

- 690 — credits in their entirety

- 703 — physics and collision detection

It adds up pretty quickly. We essentially sliced off two entire endings, because I just didn’t have any space left.

Incredibly, the token limitation used to be worse. I went searching for people talking about this, and I mostly found posts from several releases ago, when the byte limit was 32K and there weren’t any freebies in the token count — parentheses counted as two, dots counted as one.

This kind of sucks, for several reasons.

-

The most obvious way to compensate for the graphical limitations is with code: procedural generation, effects, and the like. Both of those eat up tokens fast. I spent a total of 536 tokens, 6.5% of my total space, just on adding a fog overlay.

-

I’m effectively punished for organizing code. Some 13% of my token count goes towards dotted names, i.e.,

foo.barinstead offoo_bar. -

It’s just not the kind of limitation that really inspires creativity. If you limit the number of sprites I have, okay, I can at least visually see I only have so much space and adjust accordingly. I don’t have any sense for how many tokens I’d need to write some code. If I hit the limit and the game isn’t done, that’s just a wall. I don’t have a whole lot of creative options here: I can waste time playing code golf (which here is more of an annoying puzzle than a source of inspiration), or I can delete a chunk of the game.

I looked at the most popular cartridges, and a couple depressing themes emerged. Several games are merely demos of interesting ideas that could be expanded into a game, except that the ideas alone already take half of the available tokens. Quite a few have resorted to a strong arcade vibe, with little distinction between “levels” except that there are more or different enemies. There’s a little survival crafting game which seems like it could be interesting, but it only has four objects you can build and it’s already out of tokens. Very few games have any sort of instructions (which would eat precious tokens!), and several of them have left me frustrated from the outset, until I read through the forum thread in search of someone explaining what I’m supposed to be doing.

And keep in mind, you’re starting pretty much from scratch. The most convenience the PICO-8 affords is copying a whole block of the map to the screen at once. Everything else is your problem, and it all has to fit under the cap.

The PICO-8 is really appealing overall: it has little built-in tools for creating all the resources, it’s pretty easy to do stuff with, its plaintext cartridge format makes collaboration simple, its resource limits are inspiring, it can compile to a ready-to-go browser page with no effort at all, it can even spit out short gameplay GIFs with the press of a button. And yet I’m a little apprehensive about trying anything very ambitious, now that I know how little code I’m allowed to have. The relatively small map is a bit of a shame, but the code limit is really killer.

I’ll certainly be making a few more things with this. At the same time, I can’t help but feel that some of the potential has been squeezed out of it.

![[updates]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-updates.png)