Update 2016-07-27: PICO-8 0.1.8 supports music export — export "foo%d.wav" while the music tab is selected in the editor!

Our PICO-8 game, Under Construction, contains some music that Mel composed.

The PICO-8 can only play music that you compose with the PICO-8, and it doesn’t have a music export. This posed a slight problem.

I solved that problem, and learned some things about audio along the way. None of this will be news to anyone who’s worked with sound before, but if you know as little about it as I do, you might find it as interesting as I did.

How music works in the PICO-8

The actual audio is defined in the sound editor, despite not being sound effects. There are 64 sound slots, and each sound can have up to 32 notes. Each note can have its own frequency, volume, instrument (waveform), and effect. You can also change the speed of the entire sound, which affects how long each note lasts.

There are also 64 music slots — “tracks”, perhaps? — and each track can play up to four sounds simultaneously. If you add a slow sound and a fast sound to a track, the fast sound will loop while the slow sound plays.

When a track plays to its end, the PICO-8 automatically continues to the next track and keeps playing. You can change this behavior with three flags: loop start marks the beginning of a loop, loop end will jump back to the most recent track marked with loop start, and stop will of course just stop.

A common setup with an intro and a loop might look like:

- 1

- 2

- 3, loop start

- 4

- 5, loop end

Playing track 1 will ultimately play 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 3, 4, 5, etc.

The PICO-8 does have a sound export, which just dumps 64 .wav files into the current directory, but it doesn’t have a music export. The problem is then reconstructing the music, given all the pieces.

First attempt: ffmpeg

A really nice thing about the PICO-8 is that its cartridge format isn’t some horrible binary slurry; it’s fairly straightforward hex-encoded ASCII. You can even make out parts of the spritesheet just by looking at the text representation.

Here’s some of the music from Under Construction.

1__music__

201 4a480905

301 4a080905

400 4a090805

500 08090a05

602 08090a05

7...

800 41424344

900 41424344

1000 41424344

The tracks at the end are the tracks we never used, which make it fairly easy to figure out the format here:

1FF AABBCCDD

FF is a byte representing the loop flags. (Two hex digits makes 0–255, hence, one byte.) A little experimentation makes it clear that 1 is loop start, 2 is loop end, and 4 is stop. That’s the same order the buttons appear in the UI, which is a nice confirmation.

AA, BB, CC, and DD are bytes representing the four sounds being used. Apparently a disabled sound has 64 added to it — that’s 40 in hex, which is where all the 4s came from. The sounds are numbered from 0 to 63, so it’s safe to use 64 as a flag here.

This is pretty conceptually easy, then! All I have to do is look through this list of music, figure out which sounds it uses, merge them together, then loop the results as necessary.

The obvious thing to try was ffmpeg, a command-line tool that’s ridiculously good at manipulating audio and video. It’s also ridiculously complex, but I’ve mixed audio together once before, so I at least had a vague idea of what I needed to do.

ffmpeg does interesting editors using filters, which you can string together however you want. I say “however you want”, but, ah. I tried doing this all in one step at first:

1ffmpeg -i sound9.wav -i sound5.wav -filter_complex 'amix=inputs=2,volume=2' -i sound8.wav -i sound9.wav -i sound5.wav -filter_complex 'amix=inputs=3,volume=3' -filter_complex 'concat=n=2:v=0:a=1' -ar 44100 -ac 2 out.wav

amix is the filter for mixing together some number of audio streams; concat places them one after the other. The idea here was thus: mix two sounds together (to make one track), mix three sounds together (to make another track), then concatenate the results.

Alas, this doesn’t work. Filters default to reading the first unused input file, and won’t read from other filters unless you explicitly chain them together. (I think. Feel free to read the documentation yourself and figure this out.) Explicit chaining turned out to be extremely verbose and error-prone, so I tried a simpler approach: doing it in two stages. First create all the tracks as separate files, then concatenate them together in a second pass.

And, success! I ran a script, waited a few seconds, and had a bunch of reconstructed music. I gave it to Mel, who immediately found two major problems.

- There were rather a lot of popping noises.

- An entire drum track seemed to be missing.

Whoops. I had no idea what to do about 1, but some investigation revealed that 2 was caused by different sound speeds. The drum sound in question was running at speed 1 (the fastest) alongside a rhythm sound at a much more moderate pace. The PICO-8 automatically repeats the drum for as long as necessary, but I wasn’t doing that.

This posed something of a problem. How do I repeat a track with ffmpeg? Do I have to manually concatenate it with itself some 32 times? How do I even figure out how many times I need to do that; do I invoke ffmpeg a fourth time and parse its output to get the length of each track?

This was looking a lot more painful than I’d expected, and I was pretty busy writing my post on Perlin noise, so I set this aside for a few days.

Second attempt: Python

I’d been using Python to run ffmpeg automatically, but ideally, I could load and manipulate these files directly from Python. I did a few cursory searches for audio processing libraries, and somehow kept finding the standard library wave module. I was surprised that such a thing exists, but it can’t really do anything other than read and write raw values.

I asked around a bit, but the only suggestion I got was to use numpy, an accelerated math library.

I thought that was snark at first, but… why not? Sound is a single dimension of numbers, right? I’ve done barebones things with images before, and those are two dimensions of numbers. So I gave it a shot.

It turned out to be really easy. The wave library can read samples as bytes, as well as tell you how many bytes each sample is. That’s not exactly the most convenient interface, but the PICO-8’s samples are all two-byte, so I fed all the bytes to struct.unpack to get a sequence of actual numbers. From there:

-

Looping the shorter (faster) sounds was dead easy: repeat the sequence. Thankfully, Mel used all powers of two for the speeds, so every sound’s length is an even multiple of every other sound’s length. I don’t actually know how the PICO-8 would handle a case where the same track contains, say, a 5-second sound and a 3-second sound.

-

Mixing two or more sounds was a simple matter of adding their samples together.

-

Concatenating sounds works the same way as looping a single sound: concatenate the sequences.

While figuring this out, I discovered that the PICO-8’s concept of sound “speed” is no more than a multiplier on the length of each note. Speed 1 means each note lasts 183 samples. The sounds are 22050Hz, or samples per second, so a single note at speed 1 lasts 0.0083 seconds, and the entire sound (32 notes) is 0.2656 seconds long.

Er, those are some really weird numbers, and I have no idea where they came from. I’ve never seen 183 come up before, and neither of those times mean anything to me either. If anyone has any further insight here, I would love to hear it.

But hey, this all worked beautifully! The drum sound was restored.

Oh no! The sounds still popped.

I opened the sounds in Audacity to figure out why. I don’t know anything about using Audacity, but I know it lets me look at sounds, so it seemed like a reasonable thing to try.

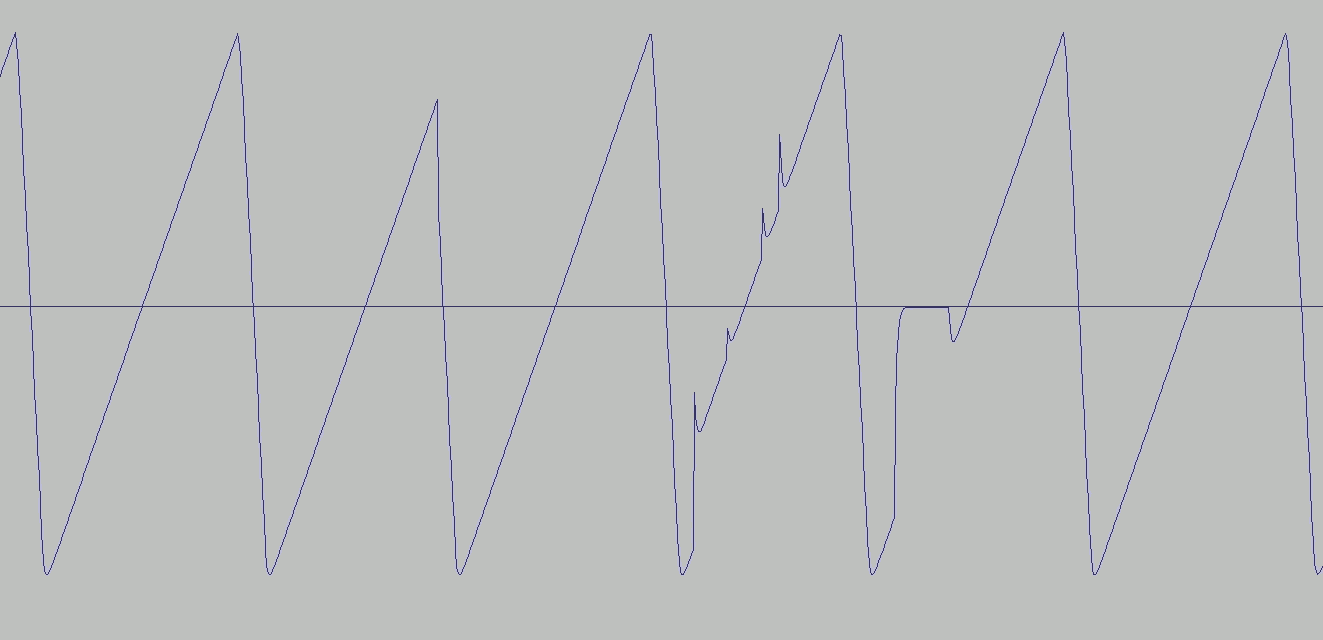

I experienced a brief and strange moment of enlightenment here. The waveform looked exactly like the instrument buttons in the PICO-8.

It’s not that I didn’t know what the pictures of waves were supposed to be — I’d only ever seen them in the context of watching someone else use a “serious” music composer to make something much more complex. I’ve opened a couple audio clips in Audacity before for various reasons, but the waveforms always looked like arbitrary garbage. I’d never seen audio so simple that I could understand exactly what was going on, so it hadn’t really clicked.

Instrument: shape of the wave. Volume: height of the wave. Note: frequency of the wave. Duration: how long the wave repeats. Plain as day. It was pretty cool.

The popping problem was also plain as day. At the point where I’d blindly stitched tracks together, there was a visible discontinuity: the wave jumped very abruptly from one value to a very different one, where everywhere else it was smooth.

I didn’t know that’s what caused popping, either. I knew about clipping, where sound is too loud for your speaker, but I didn’t know that an abrupt jump sounded like a brief moment of white noise to us. I suppose it’s like seeing bright red next to bright blue; the contrast is unnaturally sharp, so we see an ugly clash.

Anyway, I noticed that the PICO-8 mostly tries to address this problem. There’s a smooth (if slightly goofy-looking) curve where the note changes, as well as a smooth transition from zero to the first note right at the beginning. There’s just no similar transition at the end of a sound, so when two sounds are concatenated, the end of the first one will abruptly jump to the zero that begins the second one.

I was still working on the Perlin post here, so I figured I’d just slap some linear interpolation on there and hope for the best. If I interpolated the end of every sound to zero, then every track would both start and end with zero, so stitching them together should work fine.

How much do I interpolate? Well, the shortest notes are 183 samples long, and that’s 3 × 61 (seriously, what a weird number!), so I figured I’d do 61 samples.

And hey, problem solved! I then took another look and realized that the PICO-8 does exactly the same thing: linear interpolation over 61 samples. A bizarre coincidence, but it gave me the glimmer of hope that maybe I was doing the right thing here.

With that, the music was perfect. I ran the script, and after about half a minute, I had a soundtrack.

One more thing

All of the music was pop-free… except for one song. I looked at that one in Audacity and did find a discontinuity again, but this time, it was smack dab in the middle of one of the original sounds! I have no idea how this happened:

I tried to fix this by delicately drawing over it, to no avail. At least it was fairly minor.

A happy ending

I posted on the PICO-8 forums about this, and just earlier today, someone replied saying they’d had the same problem — and simply re-exporting the sounds seemed to fix it. It took me a couple tries to get perfectly clean sounds, but it did eventually work.

And now the soundtrack is on Bandcamp!

I put the code I used in a gist. I don’t want to make a repository out of this because it’s very much a throwaway and has some glaring omissions, such as:

-

I still have no idea what happens if a single track uses sounds whose lengths don’t match up. I don’t know what the PICO-8 does, and I don’t know what my script will do.

-

You can’t control how the music is arranged; the script automatically groups all the tracks into loops, and that’s what you get.

-

It might miss some of your music if you have tracks separated by a track with no sounds? I don’t know.

-

You can’t control how much the music loops; currently the loop (if any) always plays three times.

-

If a song happens to start with track 28, the loop will play seven times, because we had a song starting with that track and its loop was too short.

Ideally, the loop would automatically repeat enough to make the song some minimum length, but this took about three seconds and solved my immediate problem.

Still, if you know enough Python to fix the bits that aren’t right for what you need, it might be of use. Or perhaps I’ll fix this up and extend it into a bit more of a real PICO-8 editing tool if we make a second game!

![[articles]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-articles.png)