This is a series about Star Anise Chronicles: Cheezball Rising, an expansive adventure game about my cat for the Game Boy Color. Follow along as I struggle to make something with this bleeding-edge console!

GitHub has intermittent prebuilt ROMs, or you can get them a week early on Patreon if you pledge $4. More details in the README!

In this issue, I draw some text!

Previously: I get a Game Boy to meow.

Next: collision detection, ohh nooo…

Recap

The previous episode was a diversion (and left an open problem that I only solved after writing it), so the actual state of the game is unchanged.

Where should I actually go from here? Collision detection is an obvious place, but that’s hard. Let’s start with something a little easier: displaying scrolling dialogue text. This is likely to be a dialogue-heavy game, so I might as well get started on that now.

Planning

On any other platform, I’d dive right into it: draw a box on the screen somewhere, fill it with text.

On the Game Boy, it’s not quite that simple. I can’t just write text to the screen; I can only place tiles and sprites.

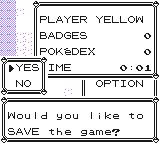

Let’s look at how, say, Pokémon Yellow handles its menu.

This looks — feels — like it’s being drawn on top of the map, and that sub-menus open on top of other menus. But it’s all an illusion! There’s no “on top” here. This is a completely flat image made up of tiles, like anything else.

This is why Pokémon has such a conspicuously blocky font: all the glyphs are drawn to fit in a single 8×8 char, so “drawing” text is as simple as mapping letters to char indexes and drawing them onto the background. The map and the menu are all on the same layer, and the game simply redraws whatever was underneath when you close something. Part of the illusion is that the game is clever enough to hide any sprites that would overlap the menu — because sprites would draw on top! (The Game Boy Color has some twiddles for controlling this layering, but Yellow was originally designed for the monochrome Game Boy.)

A critical reason that this actually works is that in Pokémon, the camera is always aligned to the grid. It scrolls smoothly while you’re walking, but you can’t actually open the menu (or pick up an item, or talk to someone, or do anything else that might show text) until you’ve stopped moving. If you could, the menu would be misaligned, because it’s part of the same grid as the map!

This poses a slight problem for my game. Star Anise isn’t locked to the grid like the Pokémon protagonist is, and unlike Link’s Awakening, I do want to have areas larger than the screen that can scroll around freely.

I know offhand that there are a couple ways to do this. One is the window, an optional extra opaque layer that draws on top of the background, with its top-left corner anchored to any point on the screen. Another is to change some display registers in the middle of the screen redrawing. If you’re thinking of any games with a status bar at the bottom or right, chances are they use the window; games with a status bar at the top have to use display register tricks.

But I don’t want to worry about any of this right now, before I even have text drawing. I know it’s possible, so I’ll deal with it later. For now, drawing directly onto the background is good enough.

Font decisions

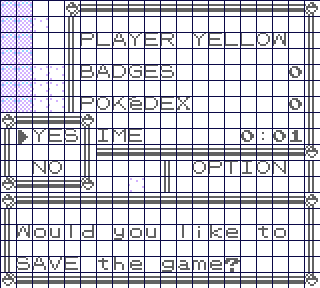

Let’s get back to the font itself. I’m not in love with the 8×8 aesthetic; what are my other options? I do like the text in Oracle of Ages, so let’s have a look at that:

Ah, this is the same approach again, except that letters are now allowed to peek up into the char above. So these are 8×16, but the letters all occupy a box that’s more like 6×9, offering much more familiar proportions. Oracle of Ages is designed for the Game Boy Color, which has twice as much char storage space, so it makes sense that they’d take advantage of it for text like this.

It’s not bad, but the space it affords is still fairly… limited. Only 16 letters will fit in a line, just as with Pokémon, and that means a lot of carefully wording things to be short and use mostly short words as well. That’s not gonna cut it for the amount of dialogue I expect to have.

(You may be wondering, as I did, how Oracle pulled off this grid-aligned textbox. In small buildings and the overworld, each room is exactly the size of the screen, so there’s no scrolling and no worry about misaligned text. But how does the game handle showing text inside a dungeon, where a room is bigger than the screen and can scroll freely? The answer is: it doesn’t! The textbox is just placed as close as possible to the position shown in this screenshot, so the edges might be misaligned by up to 4 pixels. In 20 years, I never noticed this until I thought to check how they were handling it. I’m sure there’s a lesson, here.)

What other options do I have? It seems like I’m limited to multiples of 8 here, surely. (The answer may be obvious to some of you, but shh, don’t read ahead.)

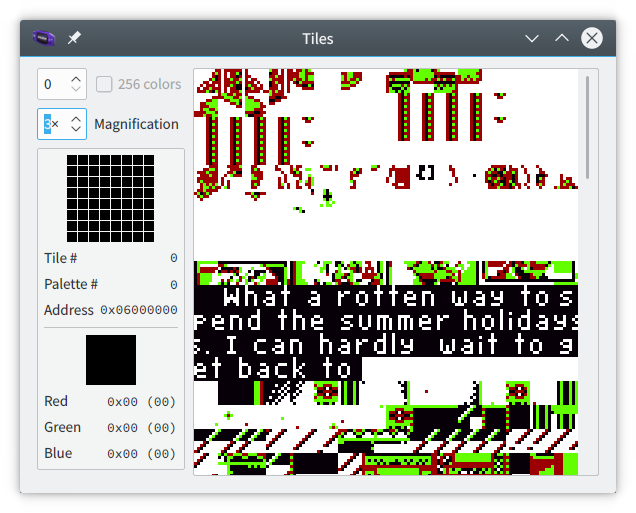

The answer lies in the very last game released for the Game Boy Color: Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Whatever deep secrets were learned during the Game Boy’s lifetime will surely be encapsulated within this, er, movie tie-in game.

Hot damn. That is a ton of text in a relatively small amount of space! And it doesn’t fit the grid! How did they do that?

The answer is… exactly how you’d think!

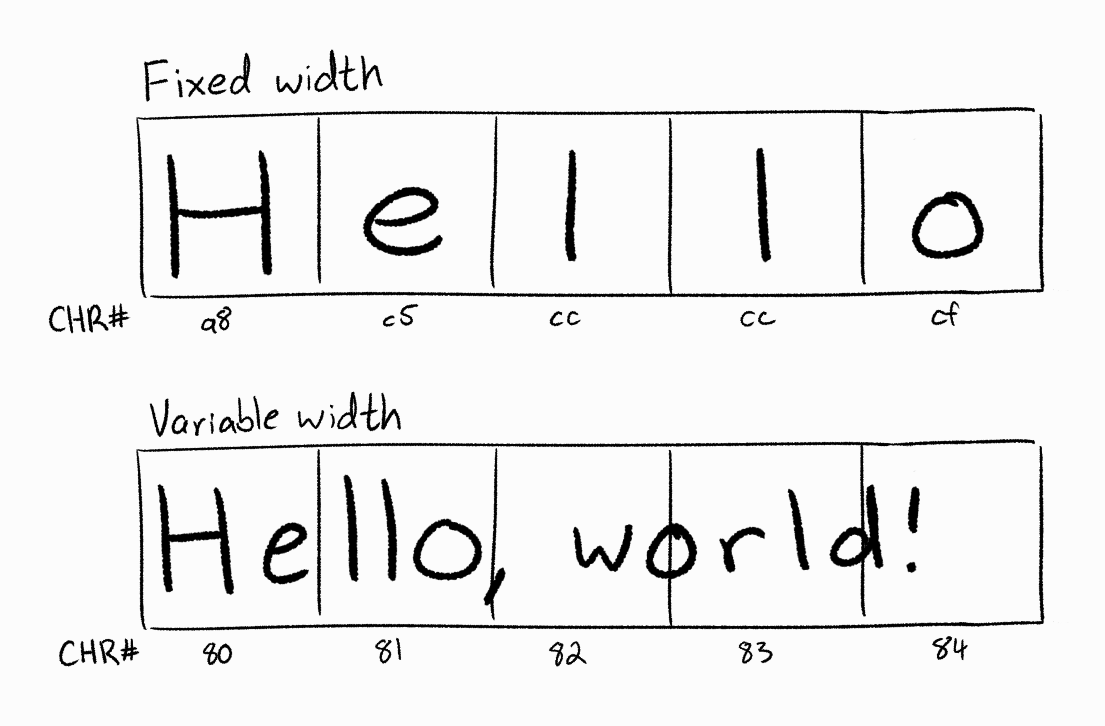

With a fixed-width font like in Pokémon and Zelda games, the entire character set is stored in VRAM, and text is drawn by drawing a string of characters. With a variable-width font like in Harry Potter, a block of VRAM is reserved for text, and text is drawn into those chars, in software. Essentially, some chars are used like a canvas and have text rendered to them on the fly. The contents of the background layer might look like this in the two cases:

Some pros of this approach:

-

Since the number of chars required is constant and the font is never loaded directly into char memory, the font can have arbitrarily many glyphs in it. Multiple fonts could be used at the same time, even. (Of course, if you have more than 256 glyphs, you’ll have to come up with a multi-byte encoding for actually storing the text…)

-

A lot more text can fit in one line while still remaining readable.

-

It has the potential to look very cool. I definitely want to squeeze every last drop of fancy-pants graphical stuff that I can from this hardware.

And, cons:

-

It’s definitely more complicated! But I only have to write the code once, and since the game won’t be doing anything but drawing dialogue while the box is up, I don’t think I’ll be in danger of blowing my CPU budget.

-

Colored text becomes a bit trickier. But still possible, so, we can worry about that later.

-

Fixed text that doesn’t scroll, like on menus and whatnot, will be something of a problem — this whole idea relies on amortizing the text rendering across multiple frames. On the other hand, this game shouldn’t have too much of that, and this sounds like a good excuse to hand-draw fixed text (which can then be much more visually interesting). At worst, I could just render the fixed text ahead of time.

Well, I’m sold. Let’s give it a shot.

First pass

Well, I want to do something on a button press, so, let’s do that.

A lot of games (older ones especially) have bugs from switching “modes” in the same frame that something else happens. I don’t entirely understand why that’s so common and should probably ask some speedrunners, but I should be fine if I do mode-switching first thing in the frame, and then start over a new frame when switching back to “world” mode. Right? Sure.

1 ; ... button reading code in main loop ...

2 bit BUTTON_A, a

3 jp nz, .do_show_dialogue

4

5 ; ... main loop ...

6

7 ; Loop again when done

8 jp vblank_loop

9

10.do_show_dialogue:

11 call show_dialogue

12 jp vblank_loop

The extra level of indirection added by .do_show_dialogue is just so the dialogue code itself isn’t responsible for knowing where the main loop point is; it can just ret.

Now to actually do something. This is a first pass, so I want to do as little as possible. I’ll definitely need a palette for drawing the text — and here I’m cutting into my 8-palette budget again, which I don’t love, but I can figure that out later. (Maybe with some shenanigans involving changing the palettes mid-redraw, even.)

1PALETTE_TEXT:

2 ; Black background, white text... then gray shadow, maybe?

3 dcolor $000000

4 dcolor $ffffff

5 dcolor $999999

6 dcolor $666666

7

8show_dialogue:

9 ; Have to disable the LCD to do video work. Later I can do

10 ; a less jarring transition

11 DisableLCD

12

13 ; Copy the palette into slot 7 for now

14 ld a, %10111000

15 ld [rBCPS], a

16 ld hl, PALETTE_TEXT

17 REPT 8

18 ld a, [hl+]

19 ld [rBCPD], a

20 ENDR

I also know ahead of time what chars will need to go where on the screen, so I can fill them in now.

Note that I really ought to blank them all out, especially since they may still contain text from some previous dialogue, but I don’t do that yet.

An obvious question is: which tiles? I think I said before that with 512 chars available, and ¾ of those still being enough to cover the entire screen in unique chars, I’m okay with dedicating a quarter of my space to UI stuff, including text. To keep that stuff “out of the way”, I’ll put them at the “end” — bank 1, starting from $80.

I’m thinking of having characters be about the same proportions as in the Oracle games. Those games use 5 rows of tiles, like this:

1top of line 1

2bottom of line 1

3top of line 2

4bottom of line 2

5blank

Since the font is aligned to the bottom and only peeks a little bit into the top char, the very top row is mostly blank, and that serves as a top margin. The bottom row is explicitly blank for a bottom margin that’s nearly the same size. The space at the top of line 2 then works as line spacing.

I’m not fixed to the grid, so I can control line spacing a little more explicitly. But I’ll get to that later and do something really simple for now, where $ff is a blank tile:

1+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

2|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|...|

3+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

4|ff|80|82|84|86|88|8a|8c|8e|90|92|94|96|...|

5+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

6|ff|81|83|85|87|89|8b|8d|8f|91|93|95|97|...|

7+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

8|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|ff|...|

9+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

This gives me a canvas for drawing a single line of text. The staggering means that the first letter will draw to adjacent chars $80 and $81, rather than distant cousins like $80 and $a0.

You may notice that the below code updates chars across the entire width of the grid, not merely the screen. There’s not really any good reason for that.

1 ; Fill text rows with tiles (blank border, custom tiles)

2 ; The screen has 144/8 = 18 rows, so skip the first 14 rows

3 ld hl, $9800 + 32 * 14

4 ; Top row, all tile 255

5 ld a, 255

6 ld c, 32

7.loop1:

8 ld [hl+], a

9 dec c

10 jr nz, .loop1

11

12 ; Text row 1: 255 on the edges, then middle goes 128, 130, ...

13 ld a, 255

14 ld [hl+], a

15 ld a, 128

16 ld c, 30

17.loop2:

18 ld [hl+], a

19 add a, 2

20 dec c

21 jr nz, .loop2

22 ld a, 255

23 ld [hl+], a

24

25 ; Text row 2: same as above, but middle is 129, 131, ...

26 ld a, 255

27 ld [hl+], a

28 ld a, 129

29 ld c, 30

30.loop3:

31 ld [hl+], a

32 add a, 2

33 dec c

34 jr nz, .loop3

35 ld a, 255

36 ld [hl+], a

37

38 ; Bottom row, all tile 255

39 ld a, 255

40 ld c, 32

41.loop4:

42 ld [hl+], a

43 dec c

44 jr nz, .loop4

Now I need to repeat all of that, but in bank 1, to specify the char bank (1) and palette (7) for the corresponding tiles. Those are the same for the entire dialogue box, though, so this part is easier.

1 ; Switch to VRAM bank 1

2 ld a, 1

3 ldh [rVBK], a

4

5 ld a, %00001111 ; bank 1, palette 7

6 ld hl, $9800 + 32 * 14

7 ld c, 32 * 4 ; 4 rows

8.loop5:

9 ld [hl+], a

10 dec c

11 jr nz, .loop5

12

13 EnableLCD

Time to get some real work done. Which raises the question: how do I actually do this?

If you recall, each 8-pixel row of a char is stored in two bytes. The two-bit palette index for each pixel is split across the corresponding bit in each byte. If the leftmost pixel is palette index 01, then bit 7 in the first byte will be 0, and bit 7 in the second byte will be 1.

Now, a blank char is all zeroes. To write a (left-aligned) glyph into a blank char, all I need to do is… well, I could overwrite it, but I could just as well OR it. To write a second glyph into the unused space, all I need to do is shift it right by the width of the space used so far, and OR it on top. The unusual split layout of the palette data is actually handy here, because it means the size of the shift matches the number of pixels, and I don’t have to worry about overflow.

10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 <- blank glyph

2

31 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 <- some byte from the first glyph

4↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

51 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 <- ORed together to display first character

6

7 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 <- some byte from the second glyph,

8 shifted by 4 (plus a kerning pixel)

9↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

101 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 <- ORed together to display first two characters

The obvious question is, well, what happens to the bits from the second character that didn’t fit? I’ll worry about that a bit later.

Oh, and finally, I’ll need a font, plus some text to display. This is still just a proof of concept, so I’ll add in a couple glyphs by hand.

1; somewhere in ROM

2font:

3; A

4 ; First byte indicates the width of the glyph, which I need

5 ; to know because the width varies!

6 db 6

7 dw `00000000

8 dw `00000000

9 dw `01110000

10 dw `10001000

11 dw `10001000

12 dw `10001000

13 dw `11111000

14 dw `10001000

15 dw `10001000

16 dw `10001000

17 dw `10001000

18 dw `00000000

19 dw `00000000

20 dw `00000000

21 dw `00000000

22 dw `00000000

23; B

24 db 6

25 dw `00000000

26 dw `00000000

27 dw `11110000

28 dw `10001000

29 dw `10001000

30 dw `10001000

31 dw `11110000

32 dw `10001000

33 dw `10001000

34 dw `10001000

35 dw `11110000

36 dw `00000000

37 dw `00000000

38 dw `00000000

39 dw `00000000

40 dw `00000000

41

42text:

43 ; Shakespeare it ain't.

44 ; Need to end with a NUL here so I know where the text

45 ; ends. This isn't C, there's no automatic termination!

46 db "ABABAAA", 0

And here we go!

1 ; ----------------------------------------------------------

2 ; Setup done! Real work begins here

3 ; b: x-offset within current tile

4 ; de: text cursor + current character tiles

5 ; hl: current VRAM tile being drawn into

6 ld b, 0

7 ld de, text

8 ld hl, $8800

9

10 ; This loop waits for the next vblank, then draws a letter.

11 ; Text thus displays at ~60 characters per second.

12.next_letter:

13 ; This is probably way more LCD disabling than is strictly

14 ; necessary, but I don't want to worry about it yet

15 EnableLCD

16 call wait_for_vblank

17 DisableLCD

18

19 ld a, [de] ; get current character

20 and a ; if NUL, we're done!

21 jr z, .done

22 inc de ; otherwise, increment

23

24 ; Get the glyph from the font, which means computing

25 ; font + 33 * a.

26 ; A little register juggling. hl points to the current

27 ; char in VRAM being drawn to, but I can only do a 16-bit

28 ; add into hl. de I don't need until the next loop,

29 ; since I already read from it. So I'm going to push de

30 ; AND hl, compute the glyph address in hl, put it in de,

31 ; then restore hl.

32 push de

33 push hl

34 ; The text is written in ASCII, but the glyphs start at 0

35 sub a, 65

36 ld hl, font

37 ld de, 33 ; 1 width byte + 16 * 2 tiles

38 ; This could probably be faster with long multiplication

39 and a

40.letter_stride:

41 jr z, .skip_letter_stride

42 add hl, de

43 dec a

44 jr .letter_stride

45.skip_letter_stride:

46 ; Move the glyph address into de, and restore hl

47 ld d, h

48 ld e, l

49 pop hl

50

51 ; Read the first byte, which is the character width. This

52 ; overwrites the character, but I have the glyph address,

53 ; so I don't need it any more

54 ld a, [de]

55 inc de

56

57 ; Copy into current chars

58 ; Part 1: Copy the left part into the current chars

59 push af ; stash width

60 ; A glyph is two chars or 32 bytes, so row_copy 32 times

61 ld c, 32

62 ; b is the next x position we're free to write to.

63 ; Incrementing it here makes the inner loop simpler, since

64 ; it can't be zero. But it also means two jumps per loop,

65 ; so, ultimately this was a pretty silly idea.

66 inc b

67.row_copy:

68 ld a, [de] ; read next row of character

69

70 ; Shift right by b places with an inner loop

71 push bc ; preserve b while shifting

72 dec b

73.shift: ; shift right by b bits

74 jr z, .done_shift

75 srl a

76 dec b

77 jr .shift

78.done_shift:

79 pop bc

80

81 ; Write the updated byte to VRAM

82 or a, [hl] ; OR with current tile

83 ld [hl+], a

84 inc de

85 dec c

86 jr nz, .row_copy

87 pop af ; restore width

88

89 ; Part 2: Copy whatever's left into the next char

90 ; TODO :)

91

92 ; Cleanup for next iteration

93 ; Undo the b increment from way above

94 dec b

95 ; It's possible I overflowed into the next column, in which

96 ; case I want to leave hl where it is: pointing at the next

97 ; column. Otherwise, I need to back it up to where it was.

98 ; Of course, I also need to update b, the x offset.

99 add a, b ; a <- new x offset

100 ; If the new x offset is 8 or more, that's actually the next

101 ; column

102 cp a, 8

103 jr nc, .wrap_to_next_tile

104 ld bc, -32 ; a < 8: back hl up

105 add hl, bc

106 jr .done_wrap

107.wrap_to_next_tile:

108 sub a, 8 ; a >= 8: subtract tile width

109 ld b, a

110.done_wrap:

111 ; Either way, store the new x offset into b

112 ld b, a

113

114 ; And loop!

115 pop de ; pop text pointer

116 jr .next_letter

117

118.done:

119 ; Undo any goofy stuff I did, and get outta here

120 EnableLCD

121 ; Remember to reset bank to 0!

122 xor a

123 ldh [rVBK], a

124 ret

Phew! That was a lot, but hopefully it wasn’t too bad. I hit a few minor stumbling blocks, but as I recall, most of them were of the “I get the conditions backwards every single time I use cp augh” flavor. (In fact, if you look at the actual commit the above is based on, you may notice that I had the condition at the very end mixed up! It’s a miracle it managed to print part of the second letter at all.)

There are a lot of caveats in this first pass, including that there’s nothing to erase the dialogue box and reshow the map underneath it. (But I might end up using the window for this anyway, so there’s no need for that.)

As a proof of concept, though, it’s a great start!

That’s the letter A, followed by the first two pixels of the letter B. I didn’t implement the part where letters spill into the next column, yet.

Guess I’d better do that!

Second pass

One of the big problems with the first pass was that I had to turn the screen off to do the actual work safely. Shifting a bunch of bytes by some amount is a little slow, since I can only shift one bit at a time and have to do it within a loop, and vblank only lasts for about 6.5% of the entire duration of the frame. If I continued like this, the screen would constantly flicker on and off every time I drew a new letter. Yikes.

I’ll solve this the same way I solve pretty much any other vblank problem: do the actual work into a buffer, then just copy that buffer during vblank. Since I intend to draw no more than one character per frame, and each character glyph is no wider than a single char column, I only need a buffer big enough to span two columns. Text covers two rows, also, so that’s four tiles total.

I also need to zero out the tile buffer when I first start drawing text — otherwise it may still have garbage left over from the last time text was displayed! — and this seems like a great opportunity to introduce a little fill function. Maybe then I’ll do the right damn thing and clear out other stuff on startup.

1; Utility code section

2

3; fill c bytes starting at hl with a

4; NOTE: c must not be zero

5fill:

6 ld [hl+], a

7 dec c

8 jr nz, fill

9 ret

10

11; ...

12

13; Stick this at a fixed nice address for now, just so it's easy

14; for me to look at and debug

15SECTION "Text buffer", WRAM0[$C200]

16text_buffer:

17 ; Text is up to 8x16 but may span two columns, so carve out

18 ; enough space for four tiles

19 ds $40

20

21show_dialogue:

22 DisableLCD

23 ; ... setup stuff ...

24 EnableLCD

25

26 ; Zero out the tile buffer

27 xor a

28 ld hl, text_buffer

29 ld c, $40

30 call fill

That first round of disabling and enabling the LCD is still necessary, because the setup work takes a little time, but I can get rid of that later too. For now, the priority is fixing the text scroll (and supporting text that spans more than one tile).

The code is the same up until I start copying the glyph into the tiles. Now it doesn’t go to VRAM, but into the buffer.

There’s another change here, too. Previously, I shifted the glyph right, letting bits fall off the right end and disappear. But the bits that drop off the end are exactly the bits that I need to draw to the next char. I could do a left shift to retrieve them, but I had a different idea: rotate the glyph instead.

Say I want to draw a glyph offset by 3 pixels. Then I want to do this:

1abcdefgh <- original glyph bits

2fghabcde <- rotate right 3

300011111 <- mask, which is just $ff shifted right 3

4

5000abcde <- rotated glyph AND mask gives the left part

6

711100000 <- mask, inverted

8fgh00000 <- rotated glyph AND inverted mask gives the right part

The time and code savings aren’t huge, exactly, and nothing else is going on while text is rendering so it’s not like time is at a premium here. But hey this feels clever so let’s do it.

1 ; Copy into current chars

2 push af ; stash width

3 ld c, 32 ; 32 bytes per row

4 ld hl, text_buffer ; new!

5 ; This is still silly.

6 inc b

7.row_copy:

8 ld a, [de] ; read next row of character

9 ; Rotate right by b - 1 pixels -- remember, b contains the

10 ; x-offset within the current tile where to start drawing

11 push bc ; preserve b while shifting

12 ld c, $ff ; initialize the mask

13 dec b

14 jr z, .skip_rotate

15.rotate:

16 ; Rotate the glyph (a), but shift the mask (c), so that the

17 ; left end of the mask fills up with zeroes

18 rrca

19 srl c

20 dec b

21 jr nz, .rotate

22.skip_rotate:

23 push af ; preserve glyph

24 and a, c ; mask right pixels

25 ; Draw to left half of text buffer

26 or a, [hl] ; OR with current tile

27 ld [hl+], a

28 ; Write the remaining bits to right half

29 ld a, c ; put mask in a...

30 cpl ; ...to invert it

31 ld c, a ; then put it back

32 pop af ; restore unmasked glyph

33 and a, c ; mask left pixels

34 ld [hl+], a ; and store them!

35 ; Clean up after myself, and loop to the next row

36 inc de ; next row of glyph

37 pop bc ; restore counter!

38 dec c

39 jr nz, .row_copy

40 pop af ; restore width

The use of the stack is a little confusing (and don’t worry, it only gets worse in later posts). Note for example that c is used as the loop counter, but since I don’t actually need its value within the body of the loop, I can push it right at the beginning and use c to hold the mask, then pop the loop counter back into place at the end.

(UPDATE: A reader points out that I don’t really need the mask at all. The rrca instruction puts the lost bit in the carry flag, so I can instead follow it with rr c, which puts the carry flag into bit 7 of c. Then I’ll end up with the right bits in c, no masking required. If I also used rra instead of rrca, then a would end up with just the left bits, and nothing needs masking at all!)

(Also, it occurs to me that I could avoid the loop entirely with a Duff’s device… but that might be a little over the top.)

This is where I first started to feel register pressure, especially when addresses eat up two of them. My options are pretty limited: I can store stuff on the stack, or store stuff in RAM. The stack is arguably harder to follow (and easier to fuck up, which I’ve done several times), but either way there’s the register ambiguity.

Which is shorter/faster? Well:

-

A

push/poppair takes 2 bytes and 7 cycles. -

Immediate writing to RAM and immediate reading back from it takes 6 bytes and 8 cycles, and can only be done with

a, so I’d probably have to copy into and out of some other register too. -

Putting an address in

hl, writing to it, then reading from it takes 5 bytes and 7 cycles, but requires that I can preservehl. (On the other hand, if I can preserve the value ofhlacross a loop or something, then it’s amortized away and the read/write is only 2 bytes and 3 cycles. But if that’s the case, chances are that I’m not under enough register pressure to need using RAM in the first place.) -

Parts of high RAM ($ff80 and up) are available for program use, and they can be read or written with the same instructions that operate on the control knobs starting at $ff00. A high RAM read and write takes 4 bytes and 6 cycles, which isn’t too bad, but once again I have to go through the

aregister so I’ll probably need some other copies.

Stack it is, then.

Anyway! Where were we. I need to now copy the buffer into VRAM.

You may have noticed that the buffer isn’t quite populated in char format. Instead, it’s populated like one big 16-pixel char, with the first 16 bits corresponding to the 16 pixels spanning both columns. VRAM, of course, expects to get all the pixels from the first column, then all the pixels from the second column. If that’s not clear, here’s what I have (where the bits are in order from left to right, top to bottom):

1AAAAAAAA BBBBBBBB <- high bits for first row of pixels

2aaaaaaaa bbbbbbbb <- low bits for first row of pixels

3... other rows ...

And here’s what I need to put in VRAM:

1AAAAAAAA <- high bits for first row of left column of pixels

2aaaaaaaa <- low bits for first row of left column of pixels

3... other rows of left column ...

4BBBBBBBB <- high bits for first row of right column of pixels

5bbbbbbbb <- low bits for first row of right column of pixels

6... other rows of right column ...

I hope that makes sense! To fix this, I use two loops (one for each column), and in each loop I copy every other byte into VRAM. That deinterlaces the buffer.

1 ; Draw the buffered tiles to vram

2 ; The text buffer is treated like it's 16 pixels wide, but

3 ; VRAM is of course only 8 pixels wide, so we need to do

4 ; this in two iterations: the left two tiles, then the right

5 pop hl ; restore hl (VRAM)

6 push af ; stash width, again

7 call wait_for_vblank ; always wait before drawing

8 push bc

9 push de

10 ; Draw the left two tiles

11 ld c, $20

12 ld de, text_buffer

13.draw_left:

14 ld a, [de]

15 ; This double inc fixes the interlacing

16 inc de

17 inc de

18 ld [hl+], a

19 dec c

20 jr nz, .draw_left

21 ; Draw the right two tiles

22 ld c, $20

23 ; This time, start from the SECOND byte, which will grab

24 ; all the bytes skipped by the previous loop

25 ld de, text_buffer + 1

26.draw_right:

27 ld a, [de]

28 inc de

29 inc de

30 ld [hl+], a

31 dec c

32 jr nz, .draw_right

33 pop de

34 pop bc

35 pop af ; restore width, again

Just about done! There’s one last thing to do before looping to the next character. If this character did in fact span both columns, then the buffer needs to be moved to the left by one column. Here’s a simplified diagram, pretending chars are 5×5 and I just drew a B:

1+-----+-----+.....+

2| A B|B | .

3|A A B| B | .

4|AAA B|B | .

5|A A B| B | .

6|A A B|B | .

7+-----+-----+.....+

The left column is completely full, so I don’t need to buffer it any more. The next character wants to draw in the last partially full column, which here is the one containing the B; it’ll also want an empty right column to overflow into if necessary.

1 ; Increment the pixel offset and deal with overflow

2 add a, b ; a <- new x offset

3 ; Regardless of whether this glyph overflowed, the VRAM

4 ; pointer was left at the beginning of the next (empty)

5 ; column, and it needs rewinding to the right column

6 ld bc, -32 ; move the VRAM pointer back...

7 add hl, bc ; ...to the start of the char

8 cp a, 8

9 jr nc, .wrap_to_next_char

10 ; The new offset is less than 8, so this character didn't

11 ; actually draw anything in the right column. Move the

12 ; VRAM pointer back a second time, to the left column,

13 ; which still has space left

14 add hl, bc

15 jr .done_wrap

16.wrap_to_next_char:

17 ; The new offset is 8 or more, so this character drew into

18 ; the next char. Subtract 8, but also shift the text buffer

19 ; by copying all the "right" chars over the "left" chars

20 sub a, 8 ; a >= 8: subtract char width

21 push hl

22 push af

23 ; The easy way to do this is to walk backwards through the

24 ; buffer. This leaves garbage in the right column, but

25 ; that's okay -- it gets overwritten in the next loop,

26 ; before the buffer is copied into VRAM.

27 ld hl, text_buffer + $40 - 1

28 ld c, $20

29.shift_buffer:

30 ld a, [hl-]

31 ld [hl-], a

32 dec c

33 jr nz, .shift_buffer

34 pop af

35 pop hl

36.done_wrap:

37 ld b, a ; either way, store into b

38

39 ; Loop

40 pop de ; pop text pointer

41 jp .next_letter

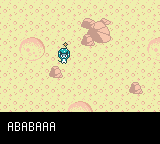

And the test run:

Hey hey, success!

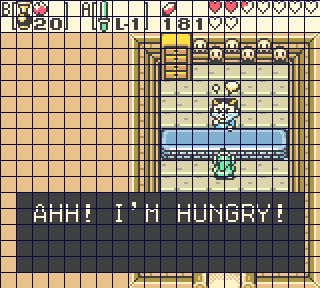

Quick diversion: Anise corruption

I didn’t mention it above because I didn’t actually use it yet, but while doing that second pass, I split the button-polling code out into its own function, read_input. I thought I might need it in dialogue as well (which has its own vblank loop and thus needs to do its own polling), but I didn’t get that far yet, so it’s still only called from the main loop.

While testing out the dialogue, I notice a teeny tiny problem.

Well, yes, obviously there’s the problem of the textbox drawing underneath the player. Which is mostly a problem because the textbox doesn’t go away, ever. I’ll worry about that later.

The other problem is that Anise’s sprite is corrupt. Again. Argh!

A little investigation suggests that, once again, I’m blowing my vblank budget. But this time, it’s a little more reasonable. Remember, I’m overwriting Anise’s sprite after handling movement. That means I do a bunch of logic followed by writing to char data. No wonder there’s a problem. I must’ve just slightly overrun vblank when I split out read_input (or checked for the dialogue button press in the first place?), since call has a teeny tiny bit of overhead.

That approach is a little inconsistent, as well. Remember how I handle OAM: I write to a buffer, which is then copied to real OAM during the next vblank. But I’m updating the sprite immediately. That means when Anise turns, the sprite updates on the very next frame, but the movement isn’t visible until the frame after that. Whoops.

So, a buffer! I could make this into a more general mechanism later, but for now I only care about fixing Anise. I can revisit this when I have, uh, a second sprite.

1; in ram somewhere

2

3anise_sprites_address:

4 dw

Now, Anise is composed of three objects, which is six chars, which is 96 bytes. The fastest way to copy bytes by hand is something like this:

1 ld hl, source

2 ld de, destination

3 ld c, 96

4.loop:

5 ld a, [hl+]

6 ld [de], a

7 inc de

8 dec c

9 jr nz, .loop

Each iteration of the loop copies 1 byte and takes 7 cycles. (It’s possible to shave a couple cycles off in some specific cases, and unrolling would save some time, but let’s stay general for now.) That’s 672 cycles, plus 10 for the setup, minus one on the final jr, for 681 total. But vblank only lasts 1140 cycles! That’s more than half the budget blown for updating a single entity. This can’t possibly work.

Enter a feature exclusive to the Game Boy Color: GDMA, or general DMA. This is similar to OAM DMA, except that it can copy (nearly) anything to anywhere. Also (unlike OAM DMA), the CPU pauses while the copy is taking place, so there’s no need to carefully time a busy loop. It’s configured by writing to five control registers (which takes 5 cycles each), and then it copies two bytes per cycle, for a total of 73 cycles. That’s 9.3 times faster. Seems worth a try.

(Note that I’m not using double-speed CPU mode yet, as an incentive to not blow my CPU budget early on. Turning that on would halve the time taken by the manual loop, but wouldn’t affect GDMA.)

GDMA has a couple restrictions: most notably, it can only copy multiples of 16 bytes, and only to/from addresses that are aligned to 16 bytes. But each char is 16 bytes, so that works out just fine.

The five GDMA registers are, alas, simply named 1 through 5. The first two are the source address; the next two are the destination address; the last is the amount to copy. Or, well, it’s the amount to copy, divided by 16, minus 1. (The high bit is reserved for turning on a different kind of DMA that operates a bit at a time during hblanks.) Writing to the last register triggers the copy.

Plugging in this buffer is easy enough, then:

1 ; Update Anise's current sprite. Use DMA here because...

2 ; well, geez, it's too slow otherwise.

3 ld hl, anise_sprites_address

4 ld a, [hl+]

5 ld [rHDMA1], a

6 ld a, [hl]

7 ld [rHDMA2], a

8 ; I want to write to $8000 which is where Anise's sprite is

9 ; hardcoded to live, and the top three bits are ignored so

10 ; that the destination is always in VRAM, so $0000 works too

11 ld a, HIGH($0000)

12 ld [rHDMA3], a

13 ld a, LOW($0000)

14 ld [rHDMA4], a

15 ; And copy!

16 ld a, (32 * 3) / 16 - 1

17 ld [rHDMA5], a

Finally, instead of actually overwriting Anise’s sprite, I write the address of the new sprite into the buffer:

1 ; Store the new sprite address, to be updated during vblank

2 ld a, h

3 ld [anise_sprites_address], a

4 ld a, l

5 ld [anise_sprites_address + 1], a

And done! Now I can walk around just fine. It looks basically like the screenshot from the previous section, so I don’t think you need a new one.

Note that this copy will always happen, since there’s no condition for skipping it when there’s nothing to do. That’s fine for now; later I’ll turn this into a list, and after copying everything I’ll simply clear the list.

Crisis averted, or at least deferred until later. Back to the dialogue!

Interlude: A font

Writing out the glyphs by hand is not going to cut it. It was fairly annoying for two letters, let alone an entire alphabet.

Nothing about this part was especially interesting. I used LÖVE’s font format, which puts all glyphs in a single horizontal strip. The color of the top-left pixel is used as a sentinel; any pixel in the top row that’s the same color indicates the start of a new glyph.

(I note that LÖVE actually recommends against using this format, but the alternatives are more complicated and require platform-specific software — whereas I can slop this format together in any image editor without much trouble.)

I then turned this into Game Boy tiles much the same way as with the sprite loader, except with the extra logic to split on the sentinel pixels and pad each glyph to eight pixels wide. I won’t reproduce the whole script here, but it’s on GitHub if you want to see it.

The font itself is, well, a font? I initially tried to give it a little personality, but that made some of the characters weirdly wide and was a bit hard to read, so I revisited it and ended up with this:

I like it, at least! The characters all have shadows built right in, and you can see at the end that I was starting to play with some non-ASCII characters. Because I can do that!

Third pass

One major obstacle remains: I can only have one line of text right now, when there’s plenty of space for two.

The obvious first thing I need to do is alter the dialogue box’s char map. It currently has a whole char’s worth of padding on every side. What a waste. I want this instead:

1+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

2|80|82|84|86|88|8a|8c|8e|90|92|94|96|...|

3+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

4|81|83|85|87|89|8b|8d|8f|91|93|95|97|...|

5+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

6|a8|aa|ac|ae|b0|b2|b4|b6|b8|ba|bc|be|...|

7+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

8|a9|ab|ad|af|b1|b3|b5|b7|b9|bb|bd|bf|...|

9+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+---+

The second row begins with char $a8 because that’s $80 + 40.

Obviously I’ll need to change the setup code to make the above pattern. But while I’m in here… remember, the setup code is the only remaining place that disables the LCD to do its work. Can I do everything within vblank instead?

I’m actually not sure, but there’s an easy way to reduce the CPU cost. Instead of setting up the whole dialogue box at once, I can do it one row at a time, starting from the bottom. That will cut the vblank pressure by a factor of four, and it’ll create a cool slide-up effect when the dialogue box opens!

Let’s give it a try. I’ll move the real code into a function, since it’ll run multiple times now. I’ll also introduce a few constants, since I’m getting tired of all the magic numbers everywhere.

1SCREEN_WIDTH_TILES EQU 20

2CANVAS_WIDTH_TILES EQU 32

3SCREEN_HEIGHT_TILES EQU 18

4CANVAS_HEIGHT_TILES EQU 32

5BYTES_PER_TILE EQU 16

6TEXT_START_TILE_1 EQU 128

7TEXT_START_TILE_2 EQU TEXT_START_TILE_1 + SCREEN_WIDTH_TILES * 2

8

9; Fill a row in the tilemap in a way that's helpful to dialogue.

10; hl: where to start filling

11; b: tile to start with

12fill_tilemap_row:

13 ; Populate bank 0, the tile proper

14 xor a

15 ldh [rVBK], a

16

17 ld c, SCREEN_WIDTH_TILES

18 ld a, b

19.loop0:

20 ld [hl+], a

21 ; Each successive tile in a row increases by 2!

22 add a, 2

23 dec c

24 jr nz, .loop0

25

26 ; Populate bank 1, the bank and palette

27 ld a, 1

28 ldh [rVBK], a

29 ld a, %00001111 ; bank 1, palette 7

30 ld c, SCREEN_WIDTH_TILES

31 dec hl

32.loop1:

33 ld [hl-], a

34 dec c

35 jr nz, .loop1

36

37 ret

Now replace the setup code with four calls to this function, waiting for vblank between successive calls.

1 ; Row 4

2 ld hl, $9800 + CANVAS_WIDTH_TILES * (SCREEN_HEIGHT_TILES - 1)

3 ld b, TEXT_START_TILE_2 + 1

4 call fill_tilemap_row

5

6 ; Row 3

7 call wait_for_vblank

8 ld hl, $9800 + CANVAS_WIDTH_TILES * (SCREEN_HEIGHT_TILES - 2)

9 ld b, TEXT_START_TILE_2

10 call fill_tilemap_row

11

12 ; Row 2

13 call wait_for_vblank

14 ld hl, $9800 + CANVAS_WIDTH_TILES * (SCREEN_HEIGHT_TILES - 3)

15 ld b, TEXT_START_TILE_1 + 1

16 call fill_tilemap_row

17

18 ; Row 1

19 call wait_for_vblank

20 ld hl, $9800 + CANVAS_WIDTH_TILES * (SCREEN_HEIGHT_TILES - 4)

21 ld b, TEXT_START_TILE_1

22 call fill_tilemap_row

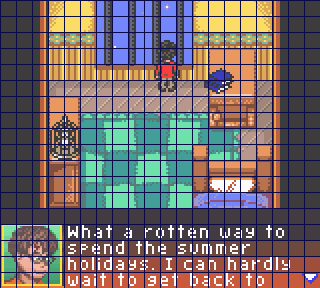

Cool. I have a full font now, too, so I might as well try it out with some more interesting text.

1SECTION "Font", ROMX

2text:

3 db "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog's back. AOOWWRRR!!!!", 0

Now I just need to— oh, hang on.

Hey, it already works! Magic.

(I did also change the initial value for the x-offset to 4 rather than 0, so the text doesn’t start against the left edge of the screen.)

Well. Not really. The code I wrote doesn’t actually know when to stop writing, so it continues off the end of the first line and onto the second. You may notice the conspicuous number of extra spaces in the new text.

Still, it looks right, and this was a lot of effort already, and it’s not actually plugged into anything yet, so I called this a success and shelved it for now. Quit while you’re ahead, right?

Future work

Obviously this is still a bit rough.

That thing where the player can walk on top of the textbox is a bit of a problem, since the same thing happens if the textbox opens while the player is near the bottom of the screen. There are a couple solutions to this, and they’ll really depend on how I end up deciding to display the box.

I actually wanted the glyphs to be drawn a little lower than normal on the top line, to add half a char or so of padding around them, but I tried it and got a buffer overrun that I didn’t feel like investigating. That’s an obvious thing to fix next time I touch this code.

What about word wrapping? I’ve written about that before and clearly have strong opinions about it, but I really don’t want to do dynamic word wrapping with a variable-width font on a Game Boy. Instead, I’ll probably store dialogue in some other format and use another converter script to do the word-wrapping ahead of time. That’ll also save me from writing large amounts of dialogue in, um, assembly. And if/when I want any fancy-pants special effects within dialogue, I can describe them with a human-readable format and then convert that to more assembly-friendly bytecode instructions.

The dialogue box still doesn’t go away, partly because it draws right on top of the map, and I don’t have any easy way to repair the map right now. I’ll probably switch to one of those other mechanisms for showing the box later that won’t require clobbering the map, and then this problem will pretty much solve itself.

What about menus? Those will either have to go inside the dialogue box (which means the question being asked isn’t visible, oof), or they’ll have to go in a smaller box above it like in Pokémon. But the latter solution means I can’t use the window or display trickery — both of those only work reliably for horizontal splits. I’m not quite sure how to handle this, yet.

And then, what of portraits? Most games get away without them by having a silent protagonist, which makes it obvious who’s talking. But Anise is anything but silent, so I need a stronger indicator. I obviously can’t overlay a big transparent portrait on the background, like I do in my LÖVE games. I think I can reseve space for them in the status bar, which will go underneath the dialogue box. I’ll have to see how it works out. Maybe I could also use a different text color for every speaker?

After all that, I can start worrying about other frills like colored text and pauses and whatever. Phew.

To be continued

That brings us up to commit a173dbb, which is slightly beyond the second release (which includes a one-line textbox)! Also that was three months ago oh dear. I think I’ll be putting out a new release soon, stay tuned!

Next time: collision detection! I am doomed.

![[process]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-process.png)