This is a series about Star Anise Chronicles: Cheezball Rising, an expansive adventure game about my cat for the Game Boy Color. Follow along as I struggle to make something with this bleeding-edge console!

GitHub has intermittent prebuilt ROMs, or you can get them a week early on Patreon if you pledge $4. More details in the README!

In this issue, I tidy up some of the gigantic mess I’ve made thusfar.

Previously: writing a main loop, and finally getting something game-like.

Next: sprite and map loading.

Recap

After only a few long, winding posts’ worth of effort, I finally have a game, if you define “game” loosely as a thing that reacts when you press buttons.

Beautiful. But to make an omelette, you need to break a few eggs, and if it’s your first omelette then you might break some glassware too. As tiny as this game is, a couple things could use improvement.

Also, for narrative purposes, it’s much more interesting to put all these miscellaneous fixes together, rather than interrupting other posts with them. I didn’t actually do all this work in one lump in this order. Apologies to the die-hard non-fiction crowd.

It's totally broken

Ah, the elephant in the room. The end of the previous post aligned with the first demo build, but if you downloaded it and tried to play it, you may have seen something that looks more like this:

I said in the beginning that I liked mGBA and would be developing against it. That’s still true — it’s open source (and I’ve actually read some of it), it’s cross-platform, and it has some debug tools built in.

I also said that emulators are primarily designed to accept correct games, not necessarily to reject incorrect games. And that’s still very true.

I discovered this problem myself a little later (after the events of the next post), while shopping around a bit for emulators explicitly focused on accuracy. The one I keep being told to use is bgb, but it’s for Windows and Wine is kind of annoying, so I was exploring my other options; I found SameBoy (primarily for Mac, but with Linux and Windows builds sans debug features) and Gambatte (cross-platform, and the core for RetroArch’s Game Boy emulation). All three of them looked like the screenshot above.

Something was going very wrong when writing to VRAM. You can’t write to VRAM while the LCD is redrawing, so the most obvious cause is that… well… maybe the LCD is redrawing during my setup code.

Remember, on an actual Game Boy, the system doesn’t immediately start running what’s on the cartridge — it scrolls in the Nintendo logo first (or on a Color, does a fancier logo with a cool fanfare). That’s done by a tiny internal program called the boot ROM, and the state of the LCD when the boot ROM hands over control is undefined. I’m sure it’s consistent, but it’s not anything in particular, and for all I know it might be when the LCD is halfway through a redraw.

(Side note: I am violating Nintendo’s game submission requirements by consistently referring to it as a “cartridge” when in fact it is properly called a Game Pak. My bad.)

So what we’re seeing above is the result of VRAM becoming locked and unlocked as the LCD draws (remember, after every row is an hblank, during which time VRAM is accessible), while I’m trying to copy blocks of data there. In fact, every emulator I’ve tried shows a slightly different form of corruption, since this problem is very sensitive to timing accuracy. Super interesting!

I could wait for vblank and try to squeeze in all my setup code there, maybe even split across several vblanks. But since this is setup code and doesn’t run during gameplay, there’s a much easier solution: turn the screen off. That’s done with a bit in the LCDC register, which I currently configure at the end of my setup code; all I need to do is move that to the beginning and clear the appropriate bit instead.

1 ld a, %00010111 ; $91 plus bit 2, minus bit 7

2 ld [$ff40], a

Then, of course, set it again once I’m done. I did this with a couple macros, since it’s only a few instructions and it seems like the kind of thing I might need again later.

1DisableLCD: MACRO

2 ld a, [$ff40]

3 and a, %0111111

4 ld [$ff40], a

5ENDM

6

7EnableLCD: MACRO

8 ld a, [$ff40]

9 or a, %10000000

10 ld [$ff40], a

11ENDM

12

13; and, of course, stick an EnableLCD at the end of setup code

Note that when the screen is off, it’s off, and there are no vblank interrupts or anything else that might be triggered by the screen’s behavior. So, you know, don’t wait for vblank while the screen’s off. When the screen turns back on, it immediately starts redrawing from the first row, so don’t try to use VRAM right away either. Finally, on the original Game Boy, do not turn off the screen when it’s not in vblank, or you might physically damage the screen. It’s fine on the Game Boy Color, but… hell, I’m gonna edit this to wait for vblank anyway. Feels kinda inappropriate to abruptly turn off the screen halfway through drawing.

Anyway, that solves my goofy corruption problems, and now the game looks the same on all of these emulators! I also reported this misbehavior, and it’s since been fixed, so recent dev builds of mGBA also correctly render garbage for the first release. See, by not targeting the most accurate emulators, I’ve caused another emulator to become more accurate!

hardware.inc

I mentioned last time that I’d adopted hardware.inc. That’s in large part because I keep producing monstrosities like the previous snippet. Here are those macros with some symbolic constants:

1DisableLCD: MACRO

2 ld a, [rLCDC]

3 and a, $ff & ~LCDCF_ON

4 ld [rLCDC], a

5ENDM

6

7EnableLCD: MACRO

8 ld a, [rLCDC]

9 or a, LCDCF_ON

10 ld [rLCDC], a

11ENDM

A breath of fresh air!

The $ff & is necessary because the argument needs to fit in a byte, but rgbasm’s integral preprocessor type is wider than a byte. I suppose I could also use LOW() here, or maybe there’s some other more straightforward solution.

Rearranging the buttons

In the previous post, I read the button states and crammed them into a single byte. I had a choice of whether to put the dpad low or the buttons low, but it didn’t seem to matter, so I picked arbitrarily: buttons high, dpad low.

It turns out I chose wrong! Also, it turns out there’s a “wrong” here! I’ve heard two compelling reasons to do it the other way. For one, hardware.inc contains constants for the bit offsets of the buttons, and it assumes the dpad is high. Why is this arbitrary data layout decision embedded in a list of hardware constants? Possibly for the second reason: on the GBA, input is available as a single word, and the lowest byte contains bits for all the buttons on the Game Boy — in the same order, with the dpad high.

So I’m switching this around and using hardware.inc‘s constants. Easy change.

Fixing vblank

My original approach to waiting for vblank seemed simple enough: loop until vblank_flag is set, clear it, then continue on.

I’ve made a slight oversight here: what if the main loop does take longer than a frame? Then a vblank interrupt will fire in the middle of it and harmlessly set vblank_flag. But when the loop finally finishes and goes to wait for vblank again, the flag will already be set, and it’ll continue on immediately — regardless of the state of the screen! Whoops.

Again, the fix is simple: clear the flag before beginning to wait.

And while I’m at it, I see other uses for waiting for vblank in the near future, so I may as well pull this out into a function.

1; idle until next vblank

2wait_for_vblank:

3 xor a ; clear the vblank flag

4 ld [vblank_flag], a

5.vblank_loop:

6 halt ; wait for interrupt

7 ld a, [vblank_flag] ; was it a vblank interrupt?

8 and a

9 jr z, .vblank_loop ; if not, keep waiting

10 ret

But wait! We’re not quite done yet; the comments have pointed out another oversight. What happens if a vblank interrupt occurs between the first ld and the halt?

1 xor a

2 ld [vblank_flag], a

3 ; vblank interrupt occurs HERE, setting the flag to 1

4 halt

The flag will already have been set, but then we’ll halt anyway and wait for the next interrupt. If that next interrupt is another vblank, all is fine. If it’s something else — like the timer, say — then the following code will see the flag is set and return immediately, even though it’s been some amount of time and we might actually be in the middle of a frame!

The same problem occurs within the loop: if we get an unrelated interrupt, ld the flag while it’s cleared, and then a vblank interrupt sets it before we test it, we’ll jump back up and wait for another interrupt which we’ll then misidentify as a vblank.

These very precise circumstances are fairly unlikely, but that’s not good enough for me. Let’s fix it:

1; idle until next vblank

2wait_for_vblank:

3 xor a ; clear the vblank flag

4 di ; avoid irq race after this ld

5 ld [vblank_flag], a

6.vblank_loop:

7 ei

8 halt ; wait for interrupt

9 di

10 ld a, [vblank_flag] ; was it a vblank interrupt?

11 and a

12 jr z, .vblank_loop ; if not, keep waiting

13 ei

14 ret

Now interrupts are disabled before we read the flag, and only enabled again immediately before the halt. (An interrupt request sent while interrupts are disabled won’t be thrown on the floor; it’s merely delayed until interrupts are enabled again.)

“Hang on,” I hear you cry. “Haven’t you just moved the goalposts? Can’t an interrupt now happen between ei and halt, just like before?”

Ah, but I have one final piece of arcane trivia up my sleeve: ei has a built-in delay and doesn’t take effect until after the next instruction. Possibly for this exact reason! This should, fingers crossed, be completely bulletproof.

Copy function

So far, I’ve done an awful lot of runtime copying by using the preprocessor. Consider the code for copying the DMA routine into HRAM:

1 ; Copy the little DMA routine into high RAM

2 ld bc, dma_copy

3 ld hl, $ff80

4 REPT dma_copy_end - dma_copy

5 ld a, [bc]

6 inc bc

7 ld [hl+], a

8 ENDR

This will repeat the ld/inc/ld dance 13 times in the built ROM. Which is fine, except that I’m about to have places where I do much more copying, and there’s only so much space in the ROM, and this is kind of ridiculous. So I guess I will finally write a copy function.

I’m calling it copy, not memcpy. What else am I going to copy, if not memory?

Attempt number 1 looked like this:

1; copy d bytes from bc to hl

2copy:

3 ld a, [bc]

4 inc bc

5 ld [hl+], a

6 dec d

7 jr z, copy

8 ret

I was then informed that it’s more idiomatic to use de as the source address and c as the count, possibly for some reason relating to the NES or SNES? I don’t remember. I’m totally on board for using c to mean a count, though, and started doing that elsewhere.

I went to change that, and actually make use of this function, and lo! I discovered a colossal bug. That last line, jr z, copy, will loop only if d was just decremented to zero. So this function will only ever copy one byte, unless you asked to copy only one byte, in which case it copies two.

This is not the first time I’ve gotten a condition backwards. I’ll get used to it eventually, I’m sure.

Oh, one other minor problem: if you ask to copy zero bytes, you’ll actually copy 256, since the zero check only comes after the decrement. (This is a recurring annoyance, actually, and makes while loops surprisingly clumsy to express.) So far I’ve only ever needed to copy a constant amount, so this hasn’t been a problem, but… I’ll just leave a comment pretending it’s a feature.

1; copy c bytes from de to hl

2; NOTE: c = 0 means to copy 256 bytes!

3copy:

4 ld a, [de]

5 inc de

6 ld [hl+], a

7 dec c

8 jr nz, copy

9 ret

And here it is in action:

1 ; Copy the little DMA routine into high RAM

2 ld de, dma_copy

3 ld hl, $FF80

4 ld c, dma_copy_end - dma_copy

5 call copy

Cool.

Of course, this is now significantly slower than the original unrolled version. The original took 13 × (2 + 2 + 2) = 78 cycles; the function adds 6 cycles for the call, 4 cycles for the ret, and 13 × (1 + 3) = 52 for the counting and jumping. As c goes to infinity, the function takes about ⅔ longer than unrolling.

If I feel like it, I could mitigate this somewhat by partially unrolling. First I’d mask off some lower bits of c — say, the lowest two — and copy that many bytes. Now the amount of copying left is a multiple of four, so I could shift c right twice and have another loop that copies four bytes at a time, amortizing the cost of the decrement and jump.

It’s not urgent enough for me to want to bother yet, and it’ll make relatively little difference for small copies like this DMA one, but I’m strongly considering it for copying a 16-bit amount.

Reset vectors

Now I have a couple utility functions like copy and wait_for_vblank. I don’t really care where they go, so I put them in their own SECTION and let the linker figure it out.

It took a while for me to notice where, exactly, the linker had put them: at $0000! These functions are small, and I have nothing explicitly placed before the interrupt handlers (which begin at $0040), so rgblink saw some empty space and filled it.

The thing is, the Game Boy has eight instructions of the form rst $xx that act as fast calls — each one jumps to a fixed low address (a “reset vector”), using less time and space than a call would. And those fixed $xx addresses are… $00, and every eight bytes afterwards.

I don’t have any immediate use for these — eight bytes isn’t a lot, though I guess copy could fit in there — but I probably don’t want arbitrary code ending up where they go, so for now I’ll stub them out like I stubbed out the interrupt handlers.

(I have been advised of one very good use for reset vectors: putting a crash handler at $38. Why? Because rst $38 is encoded as $ff, which is a fairly common byte to encounter if you accidentally jump into garbage. A lot of the Game Boy’s RAM is even initialized to $ff at startup.)

Idioms

I’m still discovering what’s considered idiomatic, but here are a couple tidbits.

The set of instructions is a little scattershot as far as arguments go. Several times early on, I wrote stuff like this:

1 ld hl, some_address

2 ld a, 133

3 ld [hl], a

But I overlooked that there are instructions for both ld [hl], n8 and ld [n16], a, so the above can be reduced to two lines. There’s no such thing as ld [n16], n8, though.

A surprising number of instructions can use [hl] directly as an operand — even inc and dec, combining fetch/mutate/store into a single instruction.

As I mentioned before, due to a bug, every halt should be followed by a nop — but rgbasm already does this by default, so I removed all the extraneous nops.

xor a is twice as short and twice as fast as ld a, 0. I mean, we’re talking about a single byte and single cycle here, but no reason not to.

(xor a really means xor a, a, but since every boolean op instruction takes a as the first argument anyway, it can be omitted. I don’t like to omit it in most cases, since xor b doesn’t mention a at all and that seems misleading, but it feels appropriate when combining a with itself.)

or a (equivalently, and a) is a quick way to test whether a is zero, since boolean ops set the zero flag.

Color

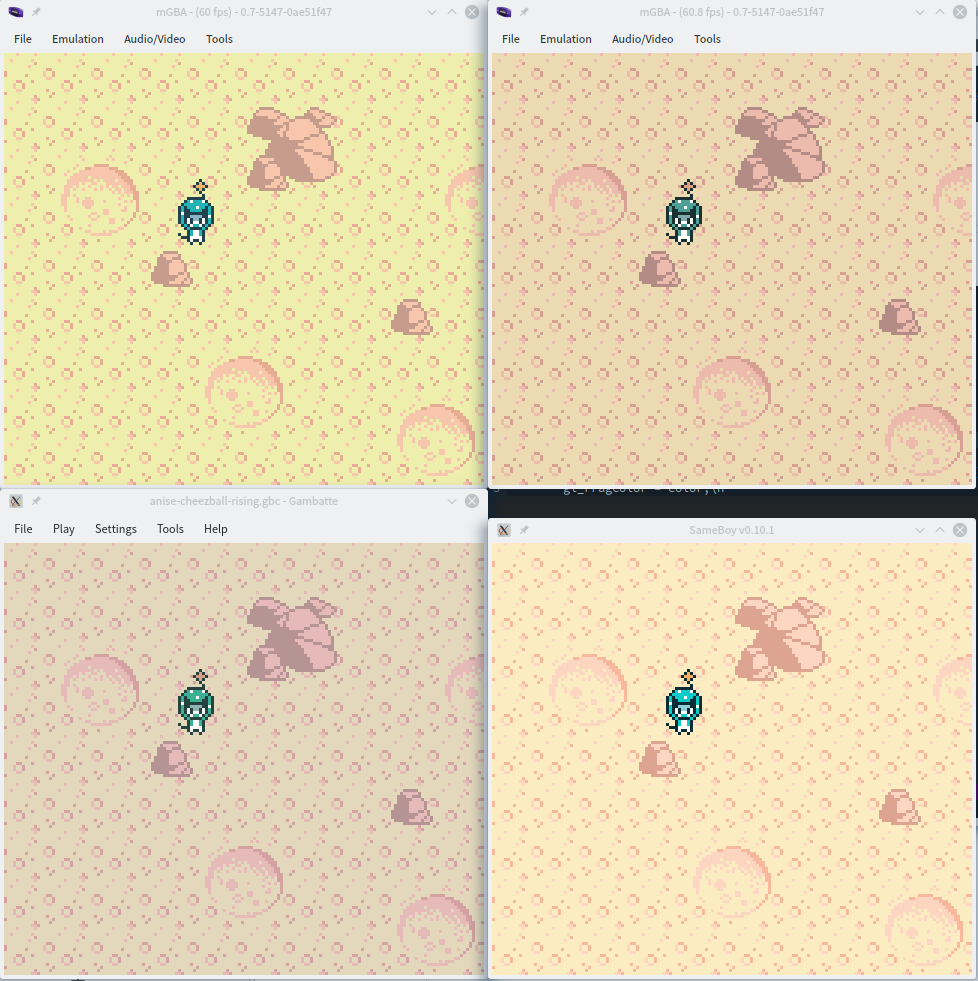

This is neither here nor there, but since this post began with emulator differences, here’s another one.

The screen you’re reading this on is almost certainly backlit, but the original Game Boy Color screen was not. A fully white pixel on a Game Boy Color is turned off — it’s the color of the screen itself, in which you can probably see your own reflection.

Which raises a tricky question: what color is that? The game thinks it’s pure white, but the screen was a sort of pale yellow. So how should it be rendered in an emulator, on a modern backlit LCD monitor?

Compounding this problem is that Game Boy Color games can also run on the Game Boy Advance, which showed the colors yet slightly differently. And, of course, even monitors may be calibrated differently, in which case it all goes out the window.

It’s interesting to see different emulators’ opinions of how to render color:

This is exactly the same ROM. The top left is mGBA out of the box, which shows colors completely unaltered — usually fairly saturated. The top right is mGBA with its “gba-colors” shader enabled, which is supposed to replicate how colors appear on a GBA screen, but seems passingly similar to a GBC too. Then on the bottom are two emulators renowned for their accuracy, here wildly disagreeing with each other.

My Game Boy Color is currently in a box somewhere, and until I can find it, I can’t be sure who’s closer. All of these are perfectly fine interpretations of the same art, though.

I may or may not use the “gba-colors” shader, and may or may not fiddle with mGBA’s color settings over time. If the colors vary a bit in future screenshots, that’s probably why.

To be continued

This post doesn’t really correspond to a particular commit very well, since it’s all little stuff I did here and there. I hope you’ve enjoyed the breather, because it’s all downhill from here. In a good way, I mean. Like a rollercoaster.

Next time: map and sprite loading, which will explain how I got from grass to the moon texture in the screenshots above!

![[process]](https://eev.ee/theme/images/category-process.png)